The edited text of a talk I gave at Christ Church New Malden on 8th February as part of a series on Christianity & Politics. A video of the talk is below.

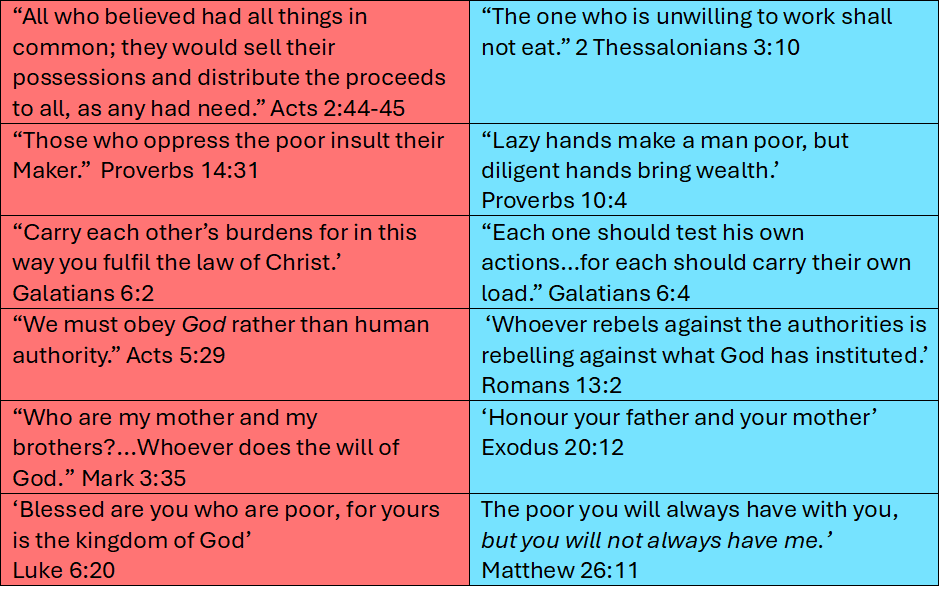

These bible readings were read by two people, one in a red top and the other in blue. These can be downloaded on a sheet at the end of the text below.

In this talk I am going to explain why my political views are on the left and also outline three challenges to the left from a Christian perspective.

As we have seen in the readings above, I believe the Bible and the Christian faith give us tensions that we need to grapple with. And these tensions are both theological and political.

My paper round

But first, I want to take you back to 1986. Rick Astley was top of the charts and Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister and I was 14.

I lived in Croydon and every morning, and along with my best mates, I did a paper round delivering newspapers to the four streets around my house. We were paid £1 a day for about an hour’s work. The newsagent, my first boss Bhupendra Patel, had a great deal going because we spent all of our wages in his shop.

The homes I delivered newspapers to were large houses owned by wealthy people. The best way to give you an idea of their politics is to tell you what newspapers they took. The most popular by far was the Daily Telegraph, often accompanied by a Daily Mail. As Bhupendra used to say ‘A Telegraph for the chap, a Mail for the wife’. I think that was pretty accurate.

On the whole of my round only one house took The Sun and only one took The Guardian. And no one took The Mirror. These were streets where Margaret Thatcher was a popular leader.

When you are growing up such social realities are often just the backdrop of your life and remain unexamined. At the time I think I considered our area quite average.

A political awakening

But I remember a specific moment when I was 16 when other realities struck me and began to change my perspective. As a teenager, I loved cricket and often matches against other clubs located in the more urban areas of south London.

During one match on a warm evening against a club near Peckham, I distinctly remember being struck by a high-rise block of flats nearby and a group of young people of a similar age to me who were hanging around on a walkway on the estate.

For some reason that I cannot explain, it suddenly dawned on me how utterly different those young people’s life experiences were to mine.

I grew up in a four-bedroom detached home on a spacious street where everyone had both front and back gardens. These young people all lived in small flats packed on top of one another and they had no garden of their own. We may have been the same age, but our lives were vastly different.

Not that I would have recognised it as such at the time but I think this single moment, a realisation half-way through a cricket match, was part of a political awakening. An awareness of inequality was influencing me – and a couple of years later I chose to study Social Work and went to Hull University in East Yorkshire.

What I learnt in Hull

I enjoyed my course but my real learning was gained by volunteering in projects out in the local community, such as children’s activity clubs on Hull’s vast housing estates such as Orchard Park. And each weekend, I went to a drop-in centre for people who were homeless and spent a couple of hours making tea and talking to men and women whose lives had been wrecked by poverty and destitution.

And in doing so, I began to understand better the structural nature of poverty and inequality. I met individuals and spent time in communities who had a very different view of Margaret Thatcher from those I had delivered newspapers to.

And after graduating, I returned to London and started working in a large hostel for homeless people in Hackney. But where I learnt the most about poverty was when I moved onto a council estate in Islington on the Essex Road called the Marquess Estate where I had volunteered on a summer holiday club for local kids.

Living on the Marquess Estate

The Marquess had a notorious reputation, a combination of poor architecture and poverty created a haven for crime, violence and anti-social behaviour.

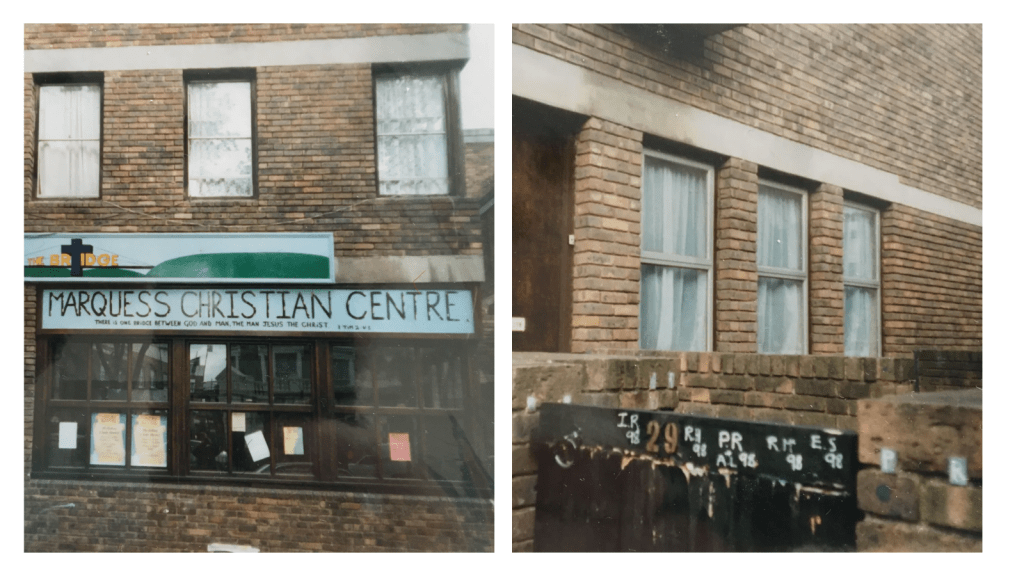

The local Baptist church which hosted the holiday club, had bought an old wine bar on the estate which had closed and turned it into the Marquess Christian Centre. The building came with two flats above it and the church youth worker lived in one of them. The year after I finished in Hull, the church asked me if I would like to move into the other flat.

In some ways it was not a particularly attractive offer. My older brother Stephen, who also helped run the holiday club, had been beaten up on the estate a few years before and I never felt particularly comfortable or safe there.

But actually it turned out to be one of the most significant decisions of my life. I was to learn more from my 2 ½ years living there about the reality of poverty than anything I had been taught on my social work course or from any job.

‘We don’t deliver there’

In my first week living there I phoned up the local take-away to have a pizza delivered. They took my order, but when I gave my address, they just said, ‘Sorry mate, we don’t deliver there’ and hung up the phone. This relatively unimportant incident impacted me because as someone from a middle-class background, it was the first time I was denied something purely based on where I lived. It helped awaken me to the reality of other people’s experiences.

I have lots of vivid memories of my time living there. I helped lead a weekly club for local children on Saturday morning who were enthusiastic and desperately keen for organised activities.

Irredeemable

But the Marquess was not an easy place to live. An intimidating group of teenagers used to regularly sit on the wall right outside my flat drinking cider and brazenly urinate into the yard outside my windows. Car crime was rife and I will never forget the loud bangs of torched cars exploding in the underground parking underneath the flat. And the kids who lined up to run over the top of parked police cars as the officers were dealing with incidents.

In the end, despite being only built in 1972 (the same year I was born), the structural problems of the Marquess were considered irredeemable and around 50% of the estate was demolished and re-designed. And this included the church centre and my flat. As people began to move out, behaviour plummeted further.

The main thing I learnt during this period was a deeper and more structural understanding of poverty. These experiences further influenced me politically to the left because they showed me the vital importance of good public investment in housing, health and education which can lift people out of poverty.

Three faces of poverty

But the poverty was also more than just material. People living there were caught in a web of disadvantage which included a deep poverty of relationships because of so many complex and chaotic family situations. And the whole estate suffered from a collective poverty of identity due to the negative reputation that the Marquess had.

And of course, any discussion of poverty is inevitably political. Using this 3-way model, the reason that resources are on the left in red is because this is the form of poverty emphasised by the left.

And this emphasis is critically important because a structural perspective on the poverty of resources is true and it’s what I learnt in Hull, on the Marquess, as well as in my years working with people affected by homelessness.

But poverty is not just a matter of resources. And its in the other two areas – of relationships and identity – which highlight some of the blind-spots of left and which the left needs to be self-critical about.

Self-righteousness

And self-critique is particularly important for those on the political left because of our tendency towards self-righteousness – an assumption that we are ‘on the side of the angels’.

This sense of assumed moral superiority is what lies behind the concept of ‘political correctness’ which seeks to police of the moral boundaries of debate. And this tendency has grown further with social media into what is called ‘woke’. Its one reason why its harder to be right-wing on social media than on the left.

The theologian Lesslie Newbigin wrote about this tendency and the influence of a Marxist frame of thought:

“For the Marxist, evil is always something external to oneself…there are only two realities – the oppressor and the oppressed. Those who identify themselves as representatives of the ‘oppressed’ are in a position to combine unlimited self-righteousness in respect of themselves with unlimited moral indignation in respect of their opponents.” (The Open Secret, p111)

But a Christian understanding cannot externalise all problems. We believe that everyone has fallen short of God’s best and that evil dwells in our hearts as well as our economic structures. We must remove the log in our own eye.

So with this in mind, I want to outline 3 areas where a Christian perspective challenges the left – and each of them connects to the readings shared earlier.

1.Personal responsibility

In the readings, we heard about people sharing all things in Acts, but then we heard St Paul’s words “The one who is unwilling to work shall not eat.” And in Galatians 6 he wrote: ‘Carry each other’s burdens’ but then only a few verses later ‘for each should carry their own load’.

We should carry burdens to help others – but our aim should be for people to take responsibility for their own load – so they can live life to the full and in turn can help others.

This is what I have seen in 30 years of working with homeless people – its why Hope into Action calls its frontline staff Empowerment Workers because our focus is to empower our tenants to take responsibility for themselves.

However much difficulty people have faced, there is limited value in reinforcing their victimhood. Darren McGarvey, a writer who is very much on the left, is a prophetic voice on this issue. He wrote this in his brilliant book Poverty Safari:

“We deny the objective truth that many people will only recover from their mental health problems, physical illnesses and addictions when they, along with correct support, accept a certain level of culpability for the choices they make…Many of the conditions of my life began to change when I got less offended by the truth: some of my problems were mine to solve.”

And I love how he sums up social and personal responsibility:

“The new frontier for individuals and movements who want to radically change society is to first recognise the need for radical change within ourselves.”

Rather then externalise all problems, we need to have welfare systems and agencies which help people to take personal responsibility, to find hope and ‘to recognise the need for radical change within ourselves’.

2. The importance of families

I used to run an emergency hostel for young homeless people in Soho in the West End of London. And family breakdown and relational poverty was by far the biggest reason why young people ended up coming through our doors.

The organisation I worked for, Centrepoint, was a great organisation in lots of ways. They produced lots of reports about youth homelessness and what the government should do, but they always avoided speaking about families or the importance of parenting despite it being such an obvious cause of many problems. And it was similar on my social work course where all the emphasis was towards government policy and structural inequality and families were barely mentioned.

Both were operating within a liberal-left culture which was far more comfortable focussing on resources rather than relationships. The left find it hard to talk about families because they fear being judgemental or seen as outdated. It’s far easier to blame the government and structural causes rather than call for individuals to act more responsibly. But this is not right because personal relationships are central to what it means to be human.

The bible teaches us from the start of Genesis that is not good for humans to be alone – we are created to be in relationship with others. And this is deeply theological because it reflects the reality of God. Genesis says ‘Let us make humans in our image’ – God is not a solitary being, waiting in heaven for us to reach him – but a trinity of relationships of Father, Son and Holy Spirit. A Father who has sent his Son to us to show us what he is like, and the Holy Spirit to help us follow this way.

This is why families are so vital – why honouring parents and caring for children is such a sacred responsibility. Not to be inward looking and only caring for our own, but as the bedrock of a compassionate society.

3. The importance of nationhood

Lastly, and perhaps most contentiously in this time, I think too often the left have not understood the importance of nationhood to many ordinary people.

Large scale immigration, especially in the last 20 years from Eastern Europe, has led many people feel their communities have changed rapidly and has not improved their lives. London has become more and more a global trading station which has destroyed community.

Some have likened the Brexit vote as like an X-ray which exposed hidden fractures in our nation’s body. And there are people stoking fears in dangerous ways and increasingly they are using Christian language. And we must challenge anything divisive or racist.

But we also should not simply dismiss people’s views on the importance of nationhood. We need to listen and take their concerns seriously – if we don’t this actually feeds racism.

Nations and borders are important because they define the area under which democracy functions. When they break down many people with least power feel most disenfranchised. We can be patriotic and care deeply about our country without being nationalistic and thinking our country is best.

And there are creative and faithful ways we can both listen and challenge. My friend Sally Mann, a Baptist Minister attended the recent carol service organised by Tommy Robinson. She strongly disagrees with him but instead of shouting him down, she went along with 2 chairs and had a constant queue of people wanting to sit, talk and pray. It was powerful and Jesus-like.

A practical and political gospel

I remain on the left politically. I believe in greater public investment to create structures and systems of social justice. I have seen how poverty blights lives and how resources need to be shared more equitably – especially when it comes to housing.

But not all social problems will be solved by distributing resources. We also need social investment in our relationships and identity. We need politics and policies which empower personal responsibility, strengthen families and create a fairer nation for all.

And I believe more than ever that the gospel is relevant to all three of these forms of poverty – and that the task of the church is to bear witness to this both practically and politically. Our gospel calls us to share resources, restore relationships and renew identities of both individuals, our communities and our whole nation.

Let’s pray and act for God’s will to be done, on earth as in heaven. Amen.

Download the above Bible readings in a dialogue format on a single sheet:

Thank you for this Jon — it’s generous, honest and genuinely searching, and the autobiographical thread that runs through it gives it some weight. The cricket match moment, the Marquess, the pizza delivery refusal — these are vivid and important. As you know I share a desire to explore how the love of Christ can penetrate our political journeys.

But I want to offer a gentle challenge to some of your central claims, because I think it deserves pushback. As you know I offer it from years of practice working within and alongside people and projects grappling with the multi-layers of poverty.

You argue that ‘the left’ (really not sure about this phrase, but i’ll go with it) is comfortable talking about resources but struggles with relationships and identity. I recognise partly the version of political struggle that you’re describing — the policy-focused, report-producing, structurally-oriented left that can speak fluently about inequality but goes quiet when the conversation turns to family, belonging, or community repair. I’ve encountered that left too.

But it isn’t the only left I’ve encountered.

Over decades of work I’ve sat with(in) projects and people rooted in left politics who have placed relationships and identity not at the margins of what they do but at the very heart of it. I’ve seen communities of people with lived experience of displacement build initiatives whose founding principles are peer support, trauma-informed practice, and leadership from within — not because a funder asked for it, but because they understood instinctively that dignity and belonging are not decorative additions to justice work, they are justice work. I’ve encountered collectives who frame the literal act of mending broken things — objects, conversations, neighbourhoods — as inseparable from the mending of people and communities. I’ve worked alongside artists and activists for whom the question of identity — who gets to tell their story, whose history has been erased, what it means to belong somewhere — is the animating centre of everything they do.

These are not people who have forgotten about relationships. These are people for whom relationship is the method, the medium, and the goal all at once.

On identity, I’d simply say this: many of the communities I currently work alongside have rarely had the luxury of ignoring it. When your sense of self has been eroded by class shame, by racism, by the stigma of disability or the disorientation of displacement, questions of identity aren’t abstract — they’re urgent. And much of the grassroots work I connect with treats them as such, quietly and without fanfare. That strikes me as identity work in the deepest sense.

I think your sharpest critique lands on a real target — the professionalised, institutionalised left, the think-tank and advocacy left that produces reports about people rather than working alongside them. That left does sometimes mistake the redistribution of resources for the whole of justice. Ironically, I often find that such manifestations of struggle are led by middle class people, or post-working class people (like myself). But I’d want us to be careful not to let that critique obscure the very different practice of the relational, community-rooted, grassroot life — which has in many ways been making your argument from the inside of what is called the left for years.

Where I think you’re most right is in the call for self-critique. The left’s tendency toward self-righteousness — what you describe through Newbigin so well — is a genuine problem, and it has cost us dearly in terms of our ability to listen to people whose concerns don’t fit our existing frameworks. Your example of your friend sitting with two chairs outside a carol service is quietly extraordinary. That posture of presence without capitulation is something all of us, left or right or Christian or secular, need more of.

For the record my deepest personal struggles are with the impact of experiencing family breakdown, changing identity/realities due to my own wealth accumalation….being slowly cooked by consumtion on all fronts.

So: yes to self-critique, yes to the importance of relationships and identity, yes to listening harder to those whose concerns we find uncomfortable. But also — let’s not write off a whole tradition of practice that has been doing exactly that work, often without recognition, for a very long time.

With respect and gratitude for the conversation.

LikeLike

Thanks Chris – really appreciate this critique and push-back. I think you are right and you shine a light on experiences that I have less of because I have spent a lot of time in the ‘professionalised’ end of things. Your words bring people to mind – and Sally and Dave Mann and Bonny Downs Church in East Ham are a great example of the kind of people who have relationships and identity embedded in their approach. For me, my biggest inspiration I think has been Bob Holman, someone very much on the left but who embodied just what you talk about through his grassroots work in Easterhouse for so long.

So thanks for the positive words and for reading and commenting.

Respect and gratitude reciprocated!

thanks, Jon

LikeLike

No worries Jon – we all need each other….Just to be clear the majority of the people I work with are not working within a faith related context….but are committed to thinking and acting with a rigour and self analysis that challenges me deeply.

LikeLike

Yes – sure. I feel like that about Darren McGarvey – I think he is brave and a really different kind of voice which is deeply challenging.

LikeLike

A great talk! I particularly like the three faces of poverty model, (Is this yours or from someone else?) The areas of overlap are particularly important. People at the Marquess were probably sitting where all three intersected.

I have become increasingly interested of late in the issue of identity. It is mainly formed by relationships, particularly by our recognition of how others see us and the roles they want us to take in relation to them. We can accept or reject these suggested identities.

Thus teenagers (and others) can reject and resist authority and choose other paths. We can accept or reject the call of others for us to become their support. We can accept or reject the call to identify as particular ethnic or social groups and expected behaviours. We can integrate within a wider community or be separate.

Thus relationships and resources help form identity, just as identity allows or constrains both of them.

One of the most important relationships we have is with God, but not everyone recognises this. As a Christian, I believe that my identity is based on what Jesus has done for us. And I attempt to follow Him and become what he has called me to become, both in relation to God and in relation to other people.

I also look to the Trinity as an example. Modern understanding of persons emphasises autonomy, independence, freedom and self-generated identity, while in the Trinity we see personhood based on on communion without loss of identity, identity based on trusting, self-giving relationships, unity that celebrates and enables difference.

This is important because it makes me think about relationships and identity differently. I have the ability and freedom to form mutual, self-giving relationships with others and develop an identity of my own using the resources I am able to access.

However, the important questions are what is being asked of me and by whom? How will this change my identity and relationships if I accept (knowing that my response will change not only me but other people as well). How do I grow into this identity? What relationships will change, what resources will it require?

I am a retired social worker, but a Christian still, so these questions remain important.

,

LikeLike

thanks Geoff for reading and commenting. These are deep questions that are hard to answer succinctly. I did develop the 3 circles model back in 2008 – I got the idea based on Jim Wallis’ model in his book Faithworks where he describes a three way model of material poverty, spiritual poverty and civic poverty. But I felt resources, relationships and identity more accurately matched what I saw – and all three have individual and collective aspects to them – and the whole thing is spiritual.

And I would agree that they all overlap and inter-penetrate each other. A lack of resources affects your relationships, your relationships affect your identity and both relationships and identity impact the resources you have.

LikeLike

wow Jon the image of MCC haven’t seen that in years. Thank you for your insight and compassion. Nigel

LikeLike

Very thought provoking, personal and initiating insightful comments. One for your book.

Jon

LikeLiked by 1 person