The Conservative Manifesto for the 2019 election said this:

“We will end the blight of rough sleeping by the end of the next Parliament.” (p.30)

With today’s announcement of a General Election in July, we will have a new Parliament this summer. And, as anyone who spends time in towns or city centres can testify, the plight of those sleeping rough is as obvious and as tragic as ever. And the last two annual official counts bear this out: in 2022 rough sleeping rose by 26% and in 2023 by 27%. Tragically, rough sleeping is nowhere near ‘ended’.

Government role

In 2018, I joined the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) as part of a team seconded from charities and local authorities to work alongside the civil servants in the Rough Sleeping Initiative (RSI). I was in the role for 4 years before returning to the voluntary sector last year.

There is no doubt that the RSI has done some great work and the response to rough sleepers in many parts of the country has been transformed. For example, the outreach teams, which engage with people on the streets, are better resourced than ever before. And over the course of 6 years, thousands of vulnerable people have been helped into emergency accommodation. Relationships and coordination between agencies have improved and the initiative was particularly vital during the pandemic as it coordinated the Everyone In initiative where 39,000 people came into emergency beds in hotels.

Failure

But, despite such progress, such initiatives must be judged on the targets they set for themselves. And by its own metrics, the campaign to end rough sleeping has failed. Battles have been won, but the overall war has been lost.

It is important we understand why this has happened. Housing is the number one social injustice in our country and we desperately need both a better public conversation about rough sleeping and a better political response to homelessness.

The reason that rough sleeping has not reduced significantly is not the fault of the team running the RSI who are as experienced and committed as any that could be assembled. And it’s not to do with a lack of partnerships, ‘joined up thinking’ or even a lack of funding.

The reason

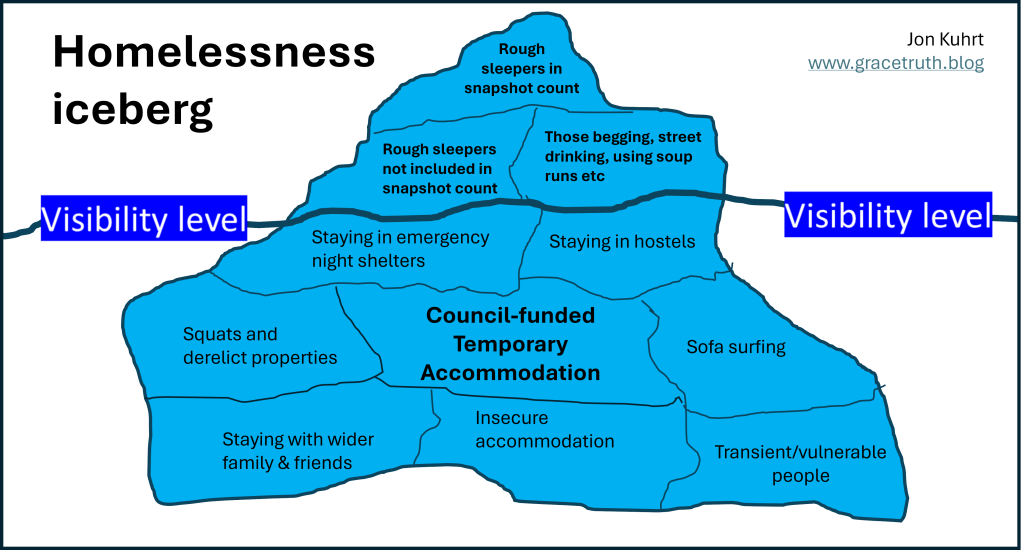

The reason it has failed is because rough sleeping is just the most visible tip of a far bigger iceberg of homelessness. It cannot be addressed as if it were a stand-alone, discrete issue because it is connected to a deep form of housing injustice affecting the whole country.

Whilst the government initiative has focused on the visible tip of the iceberg and the relatively small numbers who sleep rough, the homelessness hidden under the waterline has grown exponentially. There are now 109,000 households homeless in temporary accommodation – up 10% in a year. This includes 142,490 children – up 16,960 (14%) in a year. This is the highest since records began.

This graph illustrates the problem. The UK’s rates of homelessness are appalling in comparison with other countries but our level of rough sleeping is relatively low:

An ocean of cuts

An analogy might be helpful. Imagine the Ministry of Health sought to improve hospital care by only investing in more ambulances and Accident and Emergency departments whilst cutting funding to all other hospital departments. Some of the indicators of immediate response might improve but the overall performance of hospitals would plummet.

This is what has happened in housing. The government focus has increased in funding in emergency provision for rough sleepers, but this has been like a small island of increased funding amid an ocean of wider cuts. And all the while the water has got colder and the iceberg has grown.

Mind-boggling cost

And whilst much is made of annual snapshot counts of a relatively small number of rough sleepers, the hidden forms of homelessness have been neglected. But the cost of providing emergency accommodation is mind-boggling. It is estimated that £1.6 billion a year is being spent on emergency accommodation and these costs are bankrupting Local Authorities. Money which could be used to create more social homes is being wasted on hotels.

Rough sleeping is politically sensitive because it is so public. We need to remember that it was Margaret Thatcher’s government who started the first Rough Sleeper’s Initiative back in 1990 because even she felt the pressure of the growing numbers sleeping on the streets in the late 1980s.

But the high profile of the issue warps both the political and public response to homelessness. Rough sleeping is a tragic scandal but it’s only a fraction of wider homelessness. It cannot be addressed in isolation because it is just the most visible aspect of chronic housing injustice.

Complemented

In the early 2000s, I managed an emergency shelter in Soho, central London funded by the Rough Sleeping Unit (RSU) established by Tony Blair’s government and led by ‘Homeless Tsar’ Louise Casey. This initiative officially succeeded in its aim of reducing rough sleeping by two-thirds.

But the critical difference was its context: the RSU’s work was complemented by significant increase in wider public investment tackling social exclusion. The work to address the tip of the iceberg was accompanied by commitments to tackle the deeper social challenges.

A credible plan

In contrast, both the economic context and policies of the last 14 years have combined to deepen our severe housing crisis. The roots lie in austerity, increasing poverty, the slashing of Local Authority funding, the failure to create more social housing and address the increasing unaffordability of housing.

Also, in many areas non-UK nationals are a high proportion of those sleeping rough. As a country we have wanted the economic contribution of EU citizens but not made provision for their social needs. The restrictions on welfare entitlement have meant that those losing their employment have fallen into destitution.

Housing and homelessness should be top of the agenda for this coming election. And whilst every rough sleeper is a visible and tragic reminder of the reality of housing injustice, let’s remember that this just the tip of the homelessness iceberg. Let’s not be fooled by political rhetoric and emotive promises to ‘end rough sleeping’ without a coherent or credible plan to address the housing crisis beneath the waterline.

Great article John!

LikeLike

Thanks Ian

LikeLike

This is a excellent analysis of why we are in the position we are in regarding homelessness and how we got here. The words gather together amount to a prophetic voice. The question is, how should churches respond?

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and commenting Denis. Its a key question about what effective ways the church can lever its practical involvement into the political sphere so that we do more than just pick up the pieces. I think Housing Justice have a key role.

LikeLike

Great article as always.

I was interested though in the title “why the government has failed to end rough sleeping”. I felt this article answered some of that but my question will be “why do they not want to put money into social housing, addressing social exclusion issues, etc” I felt you told me how they didn’t end rough sleeping but didn’t let me know why they don’t want to put money towards ending it.

And from this, as elections loom, I am stuck with the question “who should I vote for?” “who is really going to change this status quo?”

LikeLike

Hi Diane – thanks for reading and commenting. I think the simple reason is that building social homes is a far deeper and significant commitment whose impact is far more hidden than just focusing on rough sleeping where the impact is noticeable and high profile. Its a question of genuine priorities and how much you really care about the more hidden social problems. Its a massive false economy though as the size of the temporary housing bill shows. I would recommend the BBC iplayer documentary Britain’s Housing Crisis.

LikeLike

Absolutely spot on – the hospital analogy is very apt. It just doesn’t work to exceptionalise rough sleeping like this. I work as rough sleeping coordinator for a Local Authority where we are fortunate to be very well resourced with rough sleeping strategy funds and they’ve certainly benefited many individuals. Yet I can’t help but think it all feels a back-to-front when you take a step back and look at it systemically – like we’ll let things get extremely dire, then come in with all the resources that the person needed all along. We’re putting all this funding towards rough sleeping, meanwhile we’re adjusting the housing register allocations policy in response to the dire shortage of social housing, making it harder than ever for your average working class person to secure affordable housing in the borough.

Also, because of these targeted resources, I often have more to offer someone if they have a rough sleeping history (particularly if they have become ‘entrenched’), so in a way we’re creating perverse incentives within the system that almost incentivise rough sleeping. That’s of course not to say anyone would choose to rough sleep, but more that if someone is already in an a quite desperate situation, perhaps moving between various precarious arrangements, considering their meagre options, they wouldn’t necessarily be wrong to believe rough sleeping would open up more options to them. We really, really don’t want to create systems that nudge people towards taking the most dangerous paths like this. It goes totally against the emphasis on prevention that everyone knows works best.

LikeLike

thanks Kate for your comment and I am particularly glad to see someone in your kind of job agreeing with me as you see it on the frontline and also could be seen to ‘gain’ from the focus on RS.

I had included a line about incentivizing rough sleeping and perverse incentives but took it out due to word count – but I saw in my adviser job the way that the focus on RS bucked the systems within LAs – in effect a RS is ‘worth more’ than someone who had not and would not sleep rough.

I completely agree about nudging people towards the wrong path – the problem is that preventing rough sleeping is politically unexciting and does not play as well on social media for the charities seeking to raise money.

LikeLike

A brilliant piece Jon – I hope you’ve sent a copy to the Minister?? I recall speaking to a European colleague a while ago who said that the UK was the only country that had written a rough sleeping strategy rather than a holistic, wide-ranging homelessness strategy and I believe it was that decision, taken several years ago and against the sector’s advice, that has let us predictably to this position. Going forward we MUST learn that prevention – and housing supply – are the fundamental building blocks to ending rough sleeping, not more temporary accommodation.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and commenting Rick. You highlight the reason I wrote it – to help ensure that the conversation going forward is more holistic and not simply focused on that tip of the iceberg. I worry that targets to ‘end rough sleeping’ such as the ones made by Boris as London Mayor or by Sajid Javed end up making people more cynical when they are nowhere near achieved.

Also, when we consider that even at the height of lock down and Everyone In etc, there were still 2000 people on the streets, I think we should be inherently cautious about ever saying we can ‘end rough sleeping’ as its probably not possible without the kind of harsh enforcement that no one swould want.

LikeLike