In the mid-1990s I worked in a large hostel in Hackney, East London for 140 homeless men and women. But the organisation I worked for had an opportunity for someone to be seconded for 5 months to a Housing Association in Kent who needed a manager to establish a new winter shelter for rough sleepers.

The location was Royal Tunbridge Wells.

Posh

I was single, flexible and quite intrigued by the challenge, so I applied and got the job. (To be honest, I think I may have been the only applicant.)

At the time, I only knew two things about Tunbridge Wells: Firstly, that my Mum had been born there as an evacuee during the war, and secondly, that it had a posh reputation.

On my first day, I was told that the shelter’s venue was an ex-old people’s home which was available for temporary use before being converted into flats. It was a beautiful building: large, central and accessible.

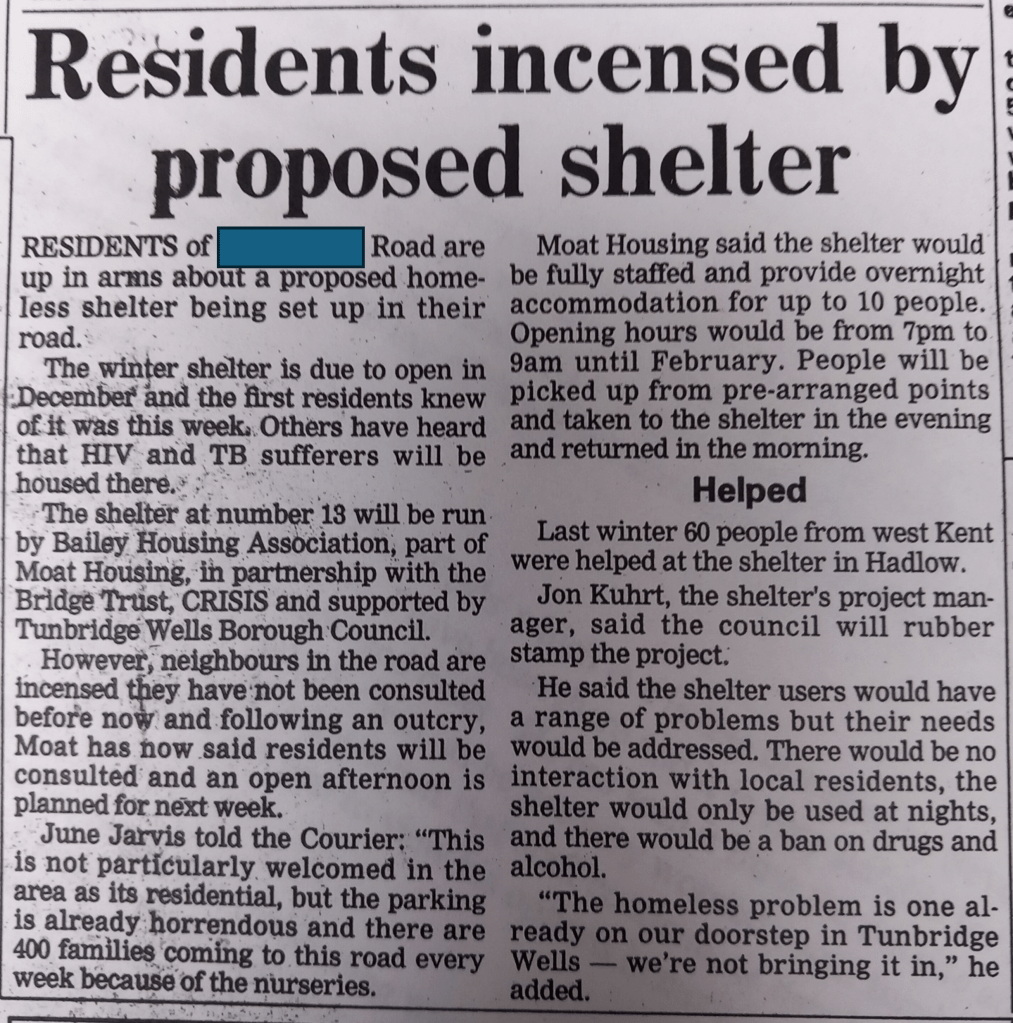

But there was one problem: the neighbours. To put it mildly, they were not happy with the idea of a homeless shelter opening in their street.

Exclusive

It turned out that our building was situated on one of Tunbridge Wells’ most expensive and exclusive roads (see above contemporary pictures of houses on the road). On my first day appointments had been lined up for me to meet some of the neighbours and the idea was that I would reassure them and ameliorate their concerns.

It turned out to be an experience that I will never forget. I was taken into a series of grand houses and introduced as ‘an expert from London’ who would somehow manage this all seamlessly. But I met people who were extremely upset and angry about the plans:

‘We moved out of London to get away from things like this’

‘Of course, the homeless should be helped. But not here – this street is completely inappropriate’

‘We have two nursery schools on this street and it will be littered with needles’

Powerful opposition

I listened carefully, nodded empathetically and tried to sound as experienced and professional as a 24 year old could. It was a form of unvarnished nimbyism (‘not in my back yard’) that would probably not be expressed so blatantly today. But the opposition was fierce and determined.

One of the neighbours was hysterically angry and had put her house up for sale in response. Another was instructing her lawyers to serve an injunction against us. In the wake of the furore, both BBC and ITV’s regional news came and filmed. And we had to hold a public meeting with the local councilors present which got increasingly tense and angry.

As I wrote in a diary I kept that winter:

‘We are facing vehement opposition but I really believe in this project. 330 people registered homeless in TW last year. It is a posh road and they are ignorant – but is this an excuse?’

Supporters

I was grateful that a number of local people did speak up in our favour. One older man who lived on the street was ostracised by his neighbours simply because he had a ‘Crisis’ sticker on his car. Rumours spread that he was ‘behind it all’.

The following week I had to attend a formal debate about the shelter at the council chambers. But because our plans involved no change of use – it was still residential accommodation, albeit for a different clientele – there was little formal mechanisms to prevent the shelter opening.

So we got the go-ahead, but not before one councilor publicly chastised me for disrespecting the Royal Town because I had been quoted on front page of the paper saying ‘The local council will rubber-stamp the project’:

Concessions

The level of opposition meant we were forced to make concessions that today seem incredible. The most controversial was that our residents could only access the shelter via a minibus with a set pick up time in the town centre – which was only 5 minutes walk away.

It was an uncomfortable compromise forced on us by the neighbours’ concern about homeless people even walking down their street.

Fear

In these weeks of politics and PR before the shelter even opened, it was not the anger and snobbishness of our opponents that most struck me. The biggest emotion I was conscious of was their fear.

Despite their wealth and security, these people seemed threatened by the very idea of homeless people being in close proximity. And it was deeper and less logical than just practical concerns about anti-social behaviour. The idea of the shelter on their street challenged their sense of order about what their street stood for. It was like a threat to their identity.

Deceitfulness of wealth

We get used to talking about the problem of poverty but we also need to talk about the problem of wealth. It brings its own form of fear.

Money has a tendency of turning people in on themselves, to guard and protect what they see as their own. It builds walls between people and increases mistrust. Its what Jesus described as ‘the deceitfulness of wealth’ which chokes our lives and makes us unfruitful.

Hugh of St Victor said:

‘The more a rich man possesses the more worry he has. He fears the failure of his revenue, he fears the violence of the mighty, doubts the honesty of his household, and lives in perpetual fear of the deception of strangers.’

I saw plenty of money in that Tunbridge Wells street, but also plenty of fear. We often describe our property and wealth as ‘our possessions’. But perhaps we don’t recognise how easily we become ‘possessed’ by them?

In the next post, I share what happened on the night we opened the shelter: The sound of breaking glass: my Tunbridge Wells Winter #2

Discover more from Grace + Truth

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thanks Jon for your reflections on your experience all those years ago, and for naming fear as the emotion – I see this in some other issues I’m dialoguing with people about today – they’re fearful of the existence of a particular group of people, and doing all they can to deny them the chance to even exist 😪 So, I find your reflections helpful as I process this other issue today 👍

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks Rohan. Yes, it was a long time ago and it was digging out a lot of old material I had kept from that time – including a diary – which jogged my memories about it all. I find understanding fear and responding to it as very central to my walk of faith.

LikeLike

You need to be keeping this sort of stuff for your memoir working within the homelessness sector Jon….Your future literary agent won’t thank you for putting up this sort of stuff for free on a blog!….In all seriousness, a very interesting article as always, AND a memoir is something you should definitely consider as an undertaking….

LikeLiked by 1 person

haha! Thanks Danny – ‘a memoir of working within the homeless sector’ might be a niche read but I hear your encouragement and will ponder it. See what you think of the second installment!

LikeLike

This is such a challenge when delivering services for people experiencing homelessness that isn’t talked about enough. I have certainly experienced the same thing in the area where I work. The difference was that it wasn’t such a salubrious area, though in these cases the narrative can be that people are simply being ‘dumped’ in the more deprived areas as the powers-that-be don’t care about exacerbating ASB issues there and wouldn’t do so in richer areas (of course, there are services in all kinds of residential areas, primarily determined by the availability of suitable premises). Whatever kind of area they are in, for one reason or another, it is not the ‘appropriate’ one!

It’s very tricky to manage, as there can of course be genuine instances of ASB like you mention in your second post in this series, yet equally these complaints often precede any residents even moving in. Residents can attract complaints even when they are not doing anything wrong as such, perhaps just visibly not fitting in, or get blamed for all and any incidents in the locality that often have nothing do to with them. It raises complex issues around community and belonging that there are no easy solutions to.

LikeLiked by 1 person