by Jon Kuhrt (first published in Third Way magazine, May 2011)

Just over ten years ago I was the manager of a sixty-bed cold weather shelter for young homeless people in Soho in central London.

The drawbacks of the location quickly became evident as it gave a base which almost encouraged many of our young residents to develop their skills in begging, selling sex and shoplifting.

After a few days of opening we would see the residents who had just moved into the shelter begging right outside the hostel and using our duvets to give the impression that they were currently sleeping rough. We used to overhear residents telling stories of their difficulties about ‘not being able to afford any of the hostels round here’ and that ‘no one would help them’ to people who stopped to talk with them.

Often the passers-by listened with real concern to the story they were told and would hand over cash to the residents. The only people who really benefitted from this exchange were Soho’s many crack and heroin dealers.

The ease of getting money through begging was not a neutral factor – it undermined the positive work we were trying to do. I remember vividly the response of one honest young person who we were urging to stay in one evening and get involved in an event we had organised. As he was leaving he turned and said to me “I’ll tell you what – if you get members of the public to walk through the hostel lounge and drop fivers and pound coins in my lap – then I’ll stay in”.

These scenarios were just a snapshot of the tragicomic scenarios that occur within the largely hidden world of homelessness. It displays the complexity of compassion and how good intentions of generous people really can be destructive rather than helpful. This was not a situation where the ends justified the means – where the young people could almost be praised for their shrewd thinking. No, in reality this actually bred further cynicism and depression in those young people because many were ashamed of what they were doing – they knew they were profiting from the naivety and kindness of others.

There is no doubt that many members of the public were trying to help these young people – but what they were doing was not actually helping them. They were seeking to show grace but the problem was one of truth – because the young people were actually presenting a false picture of their situation. They presented a case that the money would go towards food or a hostel bed – when actually it was spent on drugs. It was not that they did not have high levels of need – in fact almost all of them were profoundly damaged and disadvantaged young people who needed a high degree of support and help. But out on the street they could easily receive the last thing they needed – an incentive to remain in the downward spiral of addiction and helplessness.

GOODIES AND BADDIES?

Unfortunately, when it comes to the problems of homelessness, the compassionate acts of churches are increasingly seen as part of the problem by local authorities and larger charities. There is the view that their unfocussed work undermines the coordinated efforts of the councils and the agencies who they commission to do their work.

One current hot topic has been the issue of Soup Runs. In Westminster, the City Council recently proposed a ban on soup runs within the Victoria area which has been met with angry reaction from many grassroots groups and churches. This proposed ban comes after many years of discussion about how to coordinate the soup runs better which have had mixed results. As one senior staff member at Westminster City Council commented in frustration at a meeting I was at recently “the lack of progress with soup runs is rapidly driving me towards atheism”.

These debates tends to lapse into polarised caricatures between harsh enforcement or indiscriminate compassion. The larger agencies and local authorities can paint the churches as naïve do-gooders, locked in out-dated and inappropriate ‘old school’ approaches. On the other side some churches believe the larger agencies have sold out to the lure of government funding that they are part of a sinister agenda to clean up the streets for tourism, downplay numbers sleeping rough and corral people in against their will. Emboldened by what is seen as an opportunity to make a prophetic stand against the powerful they can portray themselves as the compassionate ‘goodies’ standing up for the poor against the corporate ‘baddies’.

This polarising creates a gap that needs bridging. Why? Because the gap does no good to the actual people who need to remain at the centre of this issue – the homeless people we are seeking to help.

THEOLOGY ON THE RUN

In order to bridge this damaging gap, we need the kind of Christian thinking that the founder of Centrepoint, Rev. Ken Leech, describes as ‘theology on the run’ – theology done in the heat of practice. This is theology which overtly integrates beliefs about God with how we live and treat others. It is powerful because truth is found when we bring together orthodoxy (right belief) with orthopraxis (right action). We cannot get away from the basic challenge that Jesus calls us to follow him. Faith is much more than mental assent – the Christian faith demands to be put into practice.

Interestingly, most homelessness agencies, whether large or small, have Christian roots. The Salvation Army and Connection at St Martin’s are obvious examples but fewer people realise the extent to which organisations like Centrepoint and Shelter were established by committed Christians. This historical connection provides an opportunity today to show the continuing relevance of Christian theology as a lens and a compass to guide our practice.

If we are to do this, we need to show a confidence and courage that is sadly often absent among Christian social activists, to speak publicly about our faith and argue its relevance. As US activist Jim Wallis says ‘faith is always personal, but never private’. Christians believe that good theology marks the road to true transformation, hope and wholeness for all people. In this age of increasing ignorance about the tenets of Christianity, it is vital that Christians live out their faith publicly. We should never settle for the deathly cosiness of private beliefs which are only expressed in sanctified settings.

THE GRACE AND TRUTH OF JESUS

The first chapter of John’s gospel states:

‘The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the One and Only, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth’ (John 1:14).

John chose these two words to sum up the qualities of Jesus: grace and truth.

Jesus embodied grace through what he taught and how he lived. He told stories of grace – a rebellious son who wasted his father’s fortune but when they returned home but were greeted with a party rather than punishment. Also of a foreigner who risked his life to care for another across the racial and religious divides. He spoke of those who were considered the least in his society actually coming first in God’s estimations. In addition to all his teaching, his example was even clearer – choosing those considered outcasts to join his group of followers, by touching those considered unclean, by breaking the religious codes to heal the disabled and helping them re-join the community. God’s grace – his unearned love, forgiveness and acceptance – is at the very centre of the gospel. This is why it is good news. God has acted within history to redeem all people, to offer another chance to everyone to be a part of the new world that God is creating. Grace has rightly been described as the best thing Christians have to share.

This is what led the early church to show such care for widows and orphans and to live as a radical community of inclusion and compassion. And this is what has led so many Christians and churches down the centuries to work with the homeless and the most marginalised and destitute people in their societies.

But the grace Jesus embodied cannot be re-cast simply as mild tolerance or uncritical acceptance of everything. His message contained a sharp edge of truth about the need for radical change: ‘I tell you the truth, no one can see the kingdom of God unless he is born again’ (John 3:3). Jesus’ warned his disciples that his message would bring conflict and division – ‘I did not come to bring peace, but a sword’ (Matt. 10:34). There is no doubting the accuracy of this warning when you consider the conflicts and persecution that the early church provoked..

So much of Jesus’ teachings focus in on the need for transformation: for people to turn from self-centredness, retribution and an obsession with status and material comfort and instead embrace generosity, justice, simplicity and dependence on God.

In the person of Jesus, therefore, grace and truth are synthesised and cannot be separated. A great succinct example is in the two-sentences he says to the woman caught in adultery who had avoided being stoned to death: ‘Then neither do I condemn you. Go now and leave your life of sin’ (John 8:11). The way of Jesus is neither easy acceptance nor narrow judgementalism – but a deeper call to transformation.

HOLDING THE TENSION

The themes of grace and truth are highly relevant when it comes to working with vulnerable people. From my experience with homeless people, I believe that over the long term, all effective transformative work must contain a blend of grace along with a holding to truth.

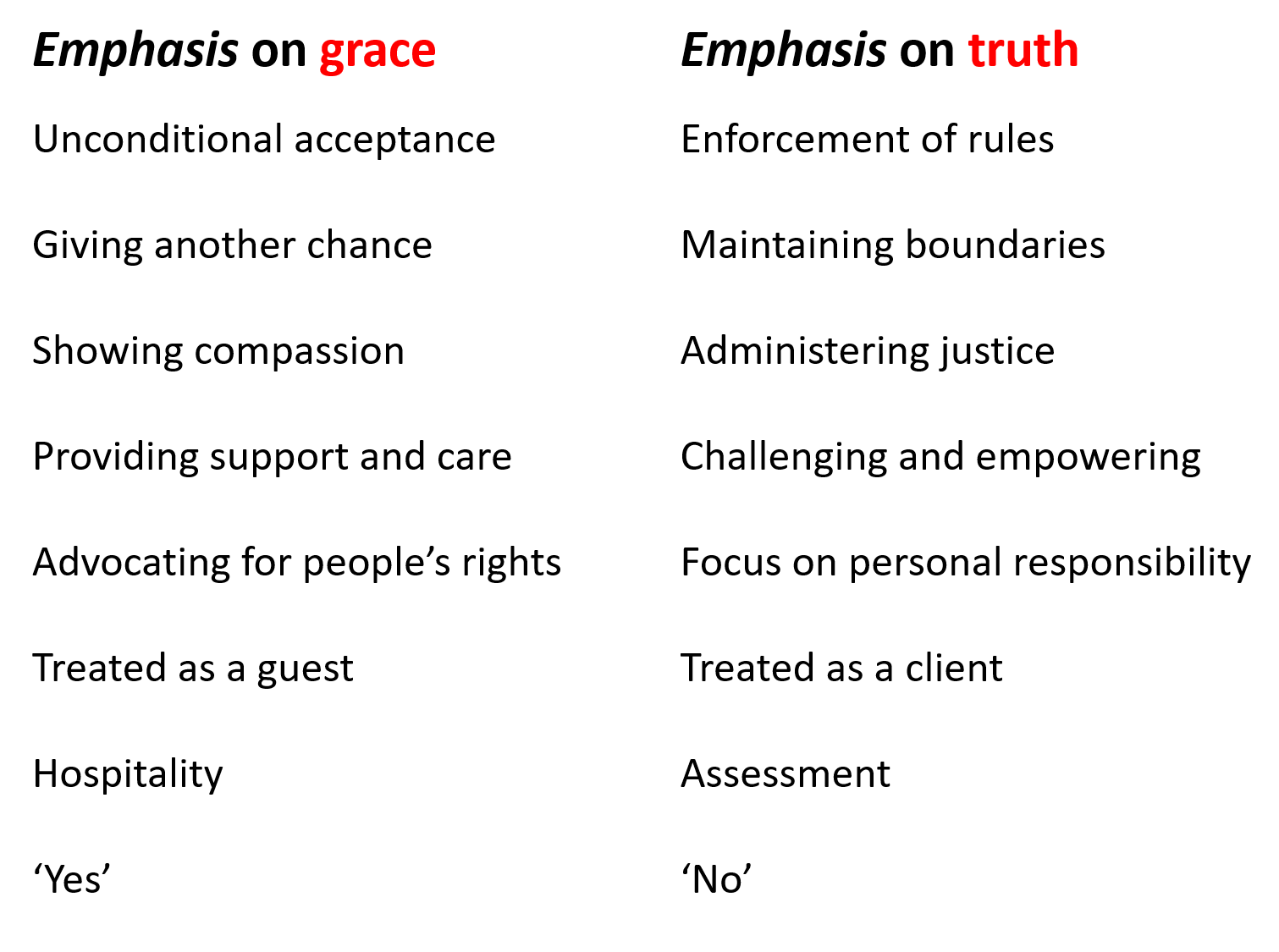

The following list of tensions display the two sides which often require careful blending in providing support to people with complex needs:

These phrases represent a ‘dialectical tension’ which needs to be continually grappled with –all sustainable and effective work will involve some degree of both sides.

These phrases represent a ‘dialectical tension’ which needs to be continually grappled with –all sustainable and effective work will involve some degree of both sides.

GRACE WITHOUT TRUTH

One criticism of Christian work with homeless people is that too much of the activity focuses on giving free meals, free accommodation, love and acceptance, running counter to other agencies’ emphasis on encouraging and empowering them to face reality and take responsibility. If there are multiple places where people can get ‘a second chance’ it can lead to people regularly being ‘saved’ without ever moving on – particularly if churches do not coordinate or communicate with other agencies about the support they give. Grace detached from truth thus becomes destructive and damaging, rather than liberating and healing.

Pastoral care within the congregations of many churches frequently faces the challenge of how to maintain care and support to vulnerable people and avoid someone with a high degree of need ‘burning out’ compassionate members of the congregation. Coordination of support and sharing information is often the way to best support and include vulnerable people. This kind of planning and communication does nothing to reduce the grace shown – on the contrary it can actually strengthen it and sustain a long term approach.

There is also the danger that completely open-access services actually create demand within groups of people who are undoubtedly needy but are not actually homeless. Fifteen years ago, I was working in a 140 bed long stay hostel in Hackney and when Crisis at Christmas opened, a large number of residents would book in for a festive holiday. Crisis was full of enthusiastic volunteers doing great work but the popular perception that all of those who turned up were current rough sleepers was more myth than reality. Since those days Crisis’ Christmas work now works in a far more coordinated way with other agencies.

It is important to say that churches across the whole country are doing great work with the homeless and vulnerable. We need to have confidence in what we can do – the kind of confidence that allows us to critique our own practice with humility, adapt it as needed and be willing to build bridges with other agencies and acknowledge the ways which our aims and purposes overlap. I believe that a balancing of grace and truth is relevant to a number of other specific issues within homelessness.

BEGGING FUNDS ADDICTION

When someone begs from someone else they in effect start a verbal or non-verbal conversation with the potential donor. In the UK today I would argue that in the vast majority of situations, this is a conversation which is not based on truth.

Often the premise presented is that the person begging needs money for food or a hostel when in fact it is virtually always going to be spent on drugs or alcohol. Sometimes this is a silent conversation aided by a cardboard sign – but over the last 10 years it has been common for many people to beg on trains using an actual conversation – in the form of speech to the carriage outlining their need for money. Often they describe the need for money to ‘get into a hostel’. I have followed up many of these requests, and they are almost always referring to hostels which do not require cash payment in this way. As I have said, they are in need but what is being presented is simply not true – and is therefore cannot be part of a step towards transformation but helps maintain a situation of physical and moral destitution. Recently I had a long conversation with someone who unsuccessfully begged from me at Clapham Junction. By the end of our talk urged me never to give to anyone begging: ‘Mate, I’ll tell you, it all goes on heroin and crack’.

A SURPLUS OF SOUP

Soup runs have been controversial for a number of years now due to many issues including the following: a) the belief that there are far too many soup runs for the numbers of rough sleepers; b) that they perpetuate street culture and create anti-social behaviour; c) that they are often conducted by groups who live considerably outside of central London and who have little knowledge of the range of services that are working with homeless people and d) that the work is driven more by the fierce commitment of the volunteers to this relatively glamorous form of activism than the need itself.

I am sympathetic to these concerns. The continuance of soup runs perpetuates the impression that the street is where help, generosity and kindness can be accessed and this inevitably draws a wide range of people who are in real need of these things. It would be far more positive for soup runs to be based within churches where social and recreational activities would be more effective. Also churches from outside central London should focus their concerns on supporting vulnerable people in their local communities – perhaps through initiatives like Food Bank or Street Pastors.

CHURCH NIGHT SHELTERS

The growth of the Church’s Night-shelter initiatives, where seven churches in a local area each provide accommodation for one night a week, is further testimony to the impressive commitment that so many Christians and churches have towards evolving new services for homeless people. I think that church night-shelters have a great role to play in meeting the needs of homeless people – especially those who are unemployed foreign nationals who have no recourse to public funds. But again, I would urge that all shelter schemes work as closely as they can with the established agencies and ensure a good and effective flow of communication to ensure that they enhance and complement the year-round work of other agencies.

A MAJOR PLAYER

Let’s be clear: the church has a major role to play in combatting homelessness. This is precisely why it’s so important that we do it right. Let me end with some specific pointers:

- TOUGH LOVE: Effective and sustained work with homeless people will always need to blend the elements of truth and grace. This is sometimes known as “tough love” but might be better termed “transformative grace” – where we are willing both to support and challenge a person in need, and not get stuck in a culture of low expectations.

- BUILD BRIDGES: the government and commissioned agencies are doing good work. We need to see our engagement and contribution to their work as mission. By building bridges between the agencies we avoid polarising the discussion.

- EMBRACE TRUTH: Christians have nothing to fear from the truth – in fact helping people face the reality of their situation, the mistakes they have made and exploring the best path to take can be the most helpful thing we can do for them.

- OFFER ADDED VALUE: Instead of duplicating the work of commissioned agencies, churches should consider ‘what can we do better than anyone else?’ Our ability to muster volunteers is the envy of the state sector, and we could bring added value to hostels or charities by offering to run recreational activities such as quiz nights and film discussion evenings, or though befriending and mentoring services.

- STAY DISTINCTIVE: Let’s put aside the baggage of the ‘singing for your soup’ era of Christian work with homeless people, and find ways to explore gospel truth with those on the margins: through chaplaincy, spirituality discussion groups, bereavement courses, Alpha courses or other opportunities to participate in the life of the church.

I will close with this wise quote from Martin Luther King:

‘The church must be reminded that it is not the master or the servant of the state, but rather the conscience of the state. It must be the guide and the critic of the state, and never its tool. If the church does not recapture its prophetic zeal, it will become an irrelevant social club without moral or spiritual authority.’ (Strength to Love, 1963)

(Please note: This article has been expanded with additional material, notably the testimony of Chris Ward, a friend of mine who slept rough for a number of years, and has been published as a booklet: Grace, Truth and Transformation)

Fantastic article Jon. Really thought-provoking. Has challenged some assumptions I have had.

LikeLike

thanks Bard of Babel – great blog name BTW.

LikeLike

Hi my name is Robert Ward from (York). I lived on the street for many years and I was olso a heroin addicted. I think the problem you had with the young ppl you had in the hostal that would go beging instead of staying in the hostal is. 1; Thay were not read them selves to leave that life behind, 2; Putting a hostal in the middle of drugs and prostitution. Is deffinatly not gong to help you any. I have not read all of the artical as at the moment I have to go and see my drug counsilor but i will.

Keep up the good work.

LikeLike

thanks Robert – testimony like yours is so important to listen to and it would be great to hear more of your experiences and what helped you – please check this post out as it might connect with you – https://jonkuhrt.wordpress.com/2011/08/30/the-best-speaker-at-greenbelt-2011/

LikeLike

A Brilliant article summing up the complexities of trying to do good. Ultimately too many of us want to make a difference but do not research the problem effectively to reach a solution. I completely agree that religious organisations can have a much wider and strategic role, and taking the braver stance of not just offering support, but challenge as well. Support without challenge feels comfortable , but ultimately leads to a sense of complacency and ineffectiveness.

LikeLike

Cheers Bolchy

LikeLike

for once , a sensible article ; a couple of things though i felt were incorrect , do you thinkthe homeless people are embarrassed about getting money ? i don’t . secondly , i always felt the crisis at christmas was a good thing as we would have residents who would go there and get as much stuff as they could even though the hostel where they were provided for them but catc gave them a 5* service as the volunteers were very generous . it is christmas after all ! i’m afraid i skipped over the godsquad bit but at least you don’t want to destroy any regency churches !

LikeLike

I think in some ways the crisis thing was good for them and I would not begrudge it – but it did not reflect reality. Crisis used to do a press release saying ‘2000 people going back on the streets’ and it simply was not the case. The good thing now is there is more honesty and connection. I don’t think the homeless people begging were that embarrassed – sometimes if we challenged them – but I think they more saw it as part of the necessary business of survival. The drug dependencies made a lot of behaviour acceptable in their own self-assessment.

LikeLike

Insightful, are you still serving the homeless.

LikeLike

?

LikeLike

yes – I work for the West London Mission working with homeless people in central London – http://www.wlm.org.uk

LikeLike

Hie John. Thanks for the timeless, insightful and practical guide to Christian living. I had personal experience of assisting some few homeless individuals with shelter, food and clothing. I was saddened that after rehabilitating for a short time they returned to the streets. My proposal had always been to equip them at least with some work to do in return for wages. However they wanted to receive food handouts and money whilst refusing the gospel I was sharing to them.I agree with you, sometimes people need “tough love” for real transformation.

LikeLike

A few thoughts – If someone is reduced to begging to survive, instead of using my moralistic judgement to determine what they are spending their money on, I can offer kindness and spare a few bucks if I have it. It is not for me to decide what they are spending their money on. I know lots of white middle class people who wouldn’t bat an eye at cheating on their taxes. I don’t see this as any different.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and commenting. This kind of comment is very common because you accept the rationale that a) people are begging to survive and b) that questioning that is ‘moralistic judgement’ and not being kind. I am an advocate of being kind – I just think we need to re-assess what kindness means. I think its far kinder to spend time talking with someone and seeking to re-affirm their worth and humanity (despite the difficulty of doing that in a brief encounter) than giving them cash which does not help them. More people giving money will only entrench people further in a desperate situation.

Your comment about middle-class people cheating on taxes is interesting. I think the similarity lies in the fact that cheating on what you owe is ultimately bad for you – just as begging is. Both are distorted forms of life. We should not be judgemental to anyone – but we cannot get away from the need to make good judgements about all these issues.

LikeLike

I am always amazed when a so-called Christian twists the Scriptures and attacks the supposedly bad character of the needy to justify not helping them.

LikeLike

Hi David

Could you say more about your experience in this area and how you are responding to the needy?

Thanks

Jon

LikeLike

Hi Jon,

Have you ever experienced any of the homeless rejecting your offer to teach them, or have you had many not-mentioned struggles? Additionally, is there a method to make them feel that Christianity isn’t being forced upon them? Some people are very anti-Christian, so I just want to know how you can counteract these feelings in order to fulfill your goals. And can emphasizing “truth”– personal responsibility and moral change — risk overlooking the immediate physical needs of those experiencing homelessness?I find this perspective really interesting, and I want to learn more!

Thank you!

LikeLike