Last Monday I gave a lecture titled Grace, Truth and the Common Good: the future of Christian Social Action, in memory of Frank Field at the London Jesuit Centre.

You can watch the lecture below. I am introduced by Jenny Sinclair who leads Together for the Common Good and the lecture starts at 5 mins and lasts 45 mins with Q&A afterwards. It is also available to listen to as a podcast and the text is below and can be downloaded here.

Introduction

It’s a real honour to be asked to give this lecture and I am grateful to Together for the Common Good and to Jenny for her belief in me and what I have to share.

It’s a particular privilege to speak in honour of Frank Field, the late Labour MP for Birkenhead.

Frank had a life-long commitment to improving the lives of people trapped in poverty – and I know you, like me, share his alarm about the deteriorating conditions here in the UK.

And Frank was willing to be honest about the complexities and realities of poverty and brave enough to say the hard things. And I know many of us are neck-deep in the complexities of this work. We need more than superficial soundbites.

And of course, Frank was a man of deep Christian conviction – the title of his memoir Politics, Poverty and Belief sums up his vocation.

I only met Frank once – we were both proud graduates of Hull University and the former Vice Chancellor David Dilks invited us both to lunch at a club near Pall Mall. Frank had read a booklet I co-wrote with my friend Chris Ward about homelessness called Grace, truth and transformation.

Chris had been homeless and had slept rough for 3 years – he was being helped by a local church but was being demanding and aggressive. The trigger moment for his recovery journey was when an older lady in the church sharply challenged him about his behaviour. As Chris put it ‘Everyone else was nice but it was her truth that made the difference’. The booklet blended Chris’s story with my theological and practical reflections.

That lunchtime in Pall Mall I was a bit in awe of Frank but he was so generous and encouraging. My thinking about grace and truth connected to his concept of ‘self-interested altruism’. As he wrote we need:

‘the important approach of balancing one great idea against another to avoid an unbalanced and even an extremist argument…our fallen natures had to be seen alongside the possibilities of our redemption.’

Frank was concerned that the reality of sinful human nature meant that effective welfare systems cannot be based simply on altruism alone – we have to work with the grain of human nature as it really is. We need grace, but we also need truth. These are themes we will explore more tonight.

I am going to start by sharing a story about how grace and truth in my work and then talk about the key challenges for Christian social action. I will unpack how a practical theology of grace and truth can help us address these challenges and I will end by proposing five directions for the future.

I will be drawing inspiration from my own evangelical tradition, the body of thinking known as Catholic Social Teaching, as well as Lesslie Newbigin and Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

Putting grace and truth to work

In 2015 I was invited to speak at a Church Urban Fund conference in the North East of England called Homelessness: are we really helping? There was considerable tension locally about the problems surrounding rough sleeping and drug use, and concerns that Christian and other groups going onto the streets to give out food and resources was making the situation worse.

The conference gathered about 120 people from charities, the local authority, community groups and churches. And this included no less than four bishops: two Roman Catholic and two Anglican.

I spoke from the passage in John 1 about Jesus being full of grace and truth and said that both these qualities need to be reflected in our work if we want it to be effective. I argued that Christian and community groups needed to accept a legitimate critique of how they operate – if their approach was ‘all grace but no truth’, and if the dynamic essentially became one-way: a donor giving to a passive recipient. Showing authentic love meant empowering people and this always involves both affirmation and kindness, and also challenge and truthfulness.

After I spoke, two of the bishops made their disapproval clear. One accusing me of being judgemental and ‘taking us back to the days of the deserving and undeserving poor’. It was an interesting experience being publicly disagreed with like that – but what reassured me was that all the formerly homeless people in the room and those with front line experience agreed with me.

A formerly homeless woman spoke honestly about how all the money she got from begging went on drugs and how proud she was of her progress when she paid an electricity bill. She described it as

‘the first time for years I hadn’t ripped anyone off.’

Another formerly homeless woman said:

‘People can’t be hand-fed, they have to help themselves. It’s alright all these agencies giving people things all the time, but you have to want to help yourself… You can throw everything at them but it’s not going to work.’

I said to the bishops that these are the stories and voices we need to hear. The tension led to a good discussion about avoiding naivety and forms of help which empower people to take ownership and responsibility. Afterwards, the Head of Housing from the local authority was in tears because she expected to get a hammering at the event and she was grateful that the complexity of the issues were being heard.

That day, grace and truth provided a dialectical framework that we grappled with. It reflects the tension in Catholic Social Teaching between the principles of solidarity – standing alongside those affected by poverty – and subsidiarity which encourages responsibility to be taken at the appropriate level, empowering people to help themselves. As Pope Benedict said:

“Subsidiarity is first and foremost a form of assistance to the human person [which] respects personal dignity by recognising in the person a subject who is always capable of giving something to others.”

Using the framework of grace and truth helps us engage with the inevitable tensions involved in the complex business of helping others. The majority of conferences, both Christian and secular, avoid really getting into these areas of tension. They therefore remain anodyne, safe, and frankly boring, because there is a fear about disagreement and grappling honestly with these issues.

But there was a nice postscript to my encounter with one of the bishops who had disagreed with me. About 6 months later he phoned me up and asked to come and see me after he had spent his sabbatical working for 3 months at The Passage, the Catholic homeless charity in Victoria. Over coffee he said to me ‘I had real problems with what you said at that conference but after my experiences on the frontline, I am now 85% in agreement with you.’

I appreciated his humility – and I said I would take 85%! And it’s an example of how the realities of frontline work is the best crucible in which to test our beliefs.

We desperately need Christian thinking which integrates belief and practice. Frankly, the world of most theological books and conferences are miles away from frontline, concrete action. But as Jesus said ‘wisdom is proved right by her actions’ (Luke 7:35) and I believe action and analysis need to be far more integrated. Ernst Troeltsch wrote

‘We theorise and construct in the eye of the storm’.

And what I will share tonight about grace and truth has developed in the stormy reality of hostels, night shelters where I have worked and volunteered with people whose lives have been devastated by poverty, trauma and addiction.

I want everything I say tonight to be anchored in real experiences and not floating in a theological or utopian neverland.

The challenges of social action

The last two decades has seen a huge growth in initiatives such as street pastors, debt centres, food banks, pantries, community supermarkets, night shelters and warm hubs. Especially since 2010, the policies of austerity have led to a boom in Christian-led social initiatives.

This expansion might be evidence of a growing Christian social conscience, but the growth of such initiatives poses important questions:

- Has enthusiasm for social action led the church to become a handmaid of the state, propping up an unjust system, filling in the gaps caused by its negligence?

- Have these projects been effective at reducing poverty in sustainable ways?

- Have they been an effective way of witnessing to the Christian faith or has social action secularised the church?

I believe that the growing levels of poverty, homelessness and destitution in the UK, and a newly elected Labour government, means we find ourselves at an important crossroads.

We need to be both confident about the importance of Christian social action and be self-critical about the consequences of what we are involved in. Sin, even unintentional, plagues all human endeavour and our social action efforts are not exempt.

I see these three issues as the key challenges we face:

1.The disconnect between charity and justice

The Brazilian Catholic Archbishop Dom Helder Camara famously said:

‘When I give bread to the poor they call me a saint. But when I ask why the poor are hungry, they call me a communist’.

It’s a quote which captures the inescapable tension between charity and justice.

As church-based social projects have grown it is common to hear people describe them in terms of ‘social justice.’ But social action and social justice are not the same thing, and most Christian activism is within a charitable framework: people giving their time and money on a voluntary basis to benefit those in need.

And such charitable approaches are often applauded by those with social and economic power because they do not call for more radical and fundamental change. In fact, power dynamics can reinforced and enhanced by charitable work.

Jesus spoke about this in Luke 22:25:

“The kings of the Gentiles lord it over them; and those who exercise authority over them call themselves Benefactors. But you are not to be like that.”

We need to ask how the growth of social action connects to questioning the underlying social and economic systems which create such need in the first place? The underlying commitment must be to a more just system.

The last 15 years has seen a whole host of new church-based homeless charities – but there are more people homeless in temporary accommodation than since records began. After a reduction during Covid, rough sleeping has risen by 27% last year and 28% the year before. These figures reflect the fundamental structural injustice of the UK housing market and our broken housing system.

The church must avoid becoming the handmaid of the state, running around filling in gaps caused by government neglect. We must not be seduced by the lure of feeling useful and settling for the transactional approaches of welfarism and of ‘projects’ which just provide handouts. This is not social justice.

We can find inspiration in the deep roots of our Judeo-Christian tradition to call for the relational justice of the Common Good. We need to focus on those elements of justice which go beyond ‘increasing benefits’ and provide a platform for mutuality and responsibility: fair and affordable housing, decent jobs and proper investment in education and re-training. True social justice enables people to find self-respect, dignity and purpose.

2. Dependency: the disconnection with empowerment

The hard truth is that not all responses to poverty are helpful or effective in addressing the problems. A huge amount has been learnt in the last few decades about what helps Majority World countries overcome poverty. The book Dead Aid by Dambisa Moyo argued powerfully that ‘aid’ given from richer countries actually served to disempower economies and deepen poverty.

We have to grapple with similar challenges in our response to poverty. US Christian activist Robert Lupton argues in his book Toxic Charity that too often social action deepens problems by creating dependency and destroying personal initiative:

‘When we do for those in need what they have the capacity to do for themselves, we disempower them.’

Lupton makes an important distinction between crisis situations and chronic problems:

‘We respond generously to stories of people in crisis, but in fact most of our charity goes to people who face predictable, solvable problems of chronic poverty. An emergency response to chronic need is at best counterproductive and, over time, is actually harmful.’

This is a problem in Christian responses to poverty in the UK too. The ‘crisis’ approach is easy to fall into because projects which provide a one-way exchange are straight-forward, easier to set up and popular with volunteers. But over the years I have been increasingly concerned to visit day centres and churches where armies of well-meaning middle-class people are running around serving people who are turned into passive recipients.

Empowering people is harder but far more important. I have come to believe that running a class to help ten people cook for themselves is better than giving out free food to a hundred people.

And the biggest need in homelessness is not to give away more resources but how we can help people maintain their accommodation, pay their rent and use their skills and strengths. We need to make a shift towards a more empowering way of working.

A key problem is that we have dependency and negative incentives baked into our welfare system. Housing Benefit particularly disincentivizes people from work and creates the ‘benefit trap’ where people are better off not working or end up taking cash-in-hand work. As Frank argued, this kind of benefits system is

“a full frontal attack on a working class moral economy that believes in work, effort, savings and honesty”.

When Frank was Minister for Welfare Reform in the Blair government in the late 1990s, he proposed a major change from a means-testing to an insurance-based system. I believe the failure to take forward these proposals is an enduring tragedy in social policy history. Such a radical re-wiring would have undoubtedly been hard, but the context of the large majority and economic boom was the moment to implement such change.

3. Secularising: the disconnection from faith

One of the constant challenges I have worked on in the last 20 years is how Christian organisations and projects maintain an active connection with the faith that birthed them. The homeless sector is packed full of agencies which used to be Christian.

Sometimes faith fades due to a lack of passion or confidence. Sometimes it is due to fear about what funders think. Sometimes it becomes fossilised when a charity’s founding inspiration and charism is neglected.

So rather than something dynamic and creative, faith often becomes just a slightly embarrassing footnote in the history of an organisation. The fruit becomes separated from the roots from which it has grown.

The missionary theologian Lesslie Newbigin has been the most significant influence on my thinking. As a student in the 1920s, he volunteered on a mission to help unemployed Welsh miners – the work had a strict liberal ethos which excluded any religious elements. But Newbigin writes in Unfinished Agenda (1993):

“as the weeks went by, I became less and less convinced that we were dealing with the real issues…these men needed some kind of faith that would fortify them for today and tomorrow against apathy and despair. Draughts and ping-pong could not provide this…they needed the Christian Faith.”

Newbigin wrote a huge amount of wise and insightful theology, but the phrase ‘draughts and ping-pong could not provide this’ has always stayed with me.

In 2013, the secular research agency, Lemos & Cranedid a survey of homeless people which found that issues of faith and spirituality were very important to many of them. Their report Lost and Found said that the ‘secular orthodoxy’ of the homeless sector more reflected staff perspectives than the homeless people themselves. The author, Carwyn Gravell, was an atheist so this could not be dismissed as Christian propaganda – and this was independent evidence of the deep relevance of faith and spirituality.

To use Paul Bickley of Theos’ milk-metaphor, we do not have to ‘skim out’ the faith element of social action. In fact, some of the most exciting work is happening where there is a ‘full-fat’ approach.

I have spent most of my working life at the skimmed and semi-skimmed end, but I felt called to work for Hope into Action because of their full-fat approach. We make no secret of our enthusiasm for integrating passionate faith within a professional working practice.

Faith in Christ is our engine: it’s what motivates staff to work for us and people to invest in our houses and it’s what motivates churches to offer friendship and community to our tenants.

And faith is so relevant to the recovery journey that so many of our tenants are on. Last year over 60% wanted to be prayed for and 16 got baptized or made a formal commitment to Christ.

As one tenant said recently at her baptism:

“I am a recovering alcoholic, 509 days sober today. The Lord did not give up on me. He saw fit to help me rebuild my life. He gave me a safe home to live in, support from Hope into Action and the generosity of Portsmouth Christian Fellowship. I owe my life to Jesus Christ and I ask that you all bear witness to my declaration of faith in him.”

Testimonies like this show how relevant faith is to the problems we seek to address. And it should never mean we are not professional – just last week Hope into Action were one of 5 agencies to win an Excellence award for from the national body, Homeless Link.

………………………

I believe that these issues – the disconnect with justice and the problems of dependency and secularisation are the three key challenges. Christian social action may have grown, but it needs to mature – and I believe that a practical theology of grace and truth is what we most need.

The grace and truth of Jesus

In John 1:14, it says: Jesus ‘came from the Father, full of grace and truth’.

The gospel writer chooses these two words to sum up Jesus: grace and truth.

We see these emphases being continually expressed throughout Jesus’ teaching and encounters in the gospel narratives.

Jesus’ grace is deeper and more confronting than mild tolerance, uncritical acceptance or ‘being kind’. His grace contains a sharp edge of truth about the need for repentance and radical change: ‘No one can see the kingdom of God unless he is born again’ (John 3:3) and ‘I did not come to bring peace, but a sword’ (Matt. 10:34).

This is seen in his encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well. Jesus affirms the woman by asking for her to give him a drink, but then he speaks challenging truth into her life. The grace and truth of Jesus is neither easy acceptance or harsh judgement. And this empowers her to share this life changing message with her whole community.

In the parable of the prodigal son, before the destitute son is received with such grace and forgiveness by his father, he comes to his senses, faces what he has done, repents and returns home. His own embrace of the truth leads to the Father’s embrace of grace.

In Jesus grace and truth are synthesized: his grace invites us to live in reality, to take responsibility, to embrace the truth about ourselves.

The deepest truth is the reality of God’s grace. But this grace demands truthfulness.

Practical applications

I would argue that a general weakness of social action is an imbalance of too much grace and not enough on truth. And grace without truth becomes what Dietrich Bonhoeffer described as ‘cheap grace’ – where the church

“showers blessings with generous hands, without asking questions or fixing limits… where “the consolations of religion are thrown away at cut prices.”

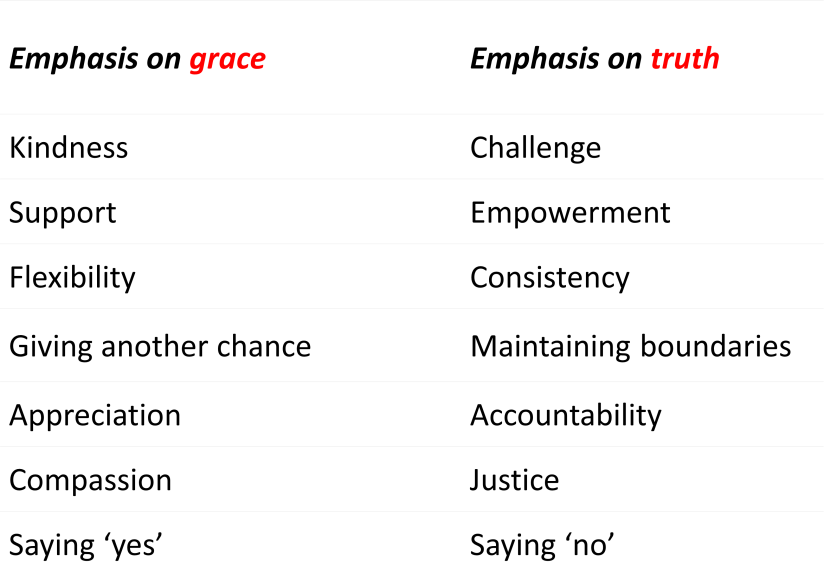

But what does this mean for our face to face work with people who need help? About 12 years ago, I developed this chart to set out the grace-truth tension in terms of a practical response to people who are homeless:

The emphasis of grace is shown in the left-hand column: unconditional acceptance, giving another chance, showing compassion, support and care, advocating for their rights and saying ‘yes’ to people. Too often people think this is all that is involved in helping others, showing love, being ‘Christian’.

But this is not the whole picture – in many ways the left side is the easy bit.

The right side of the chart is just as important. As well as acceptance, rules need enforcing; as well as giving chances, boundaries need to be maintained; as well as compassion, justice must be upheld; as well as support, people often need challenging and empowering; as well as advocating for people’s rights, we also need to emphasise their personal responsibilities.

The management of such tensions has been the basis of my daily work for many years.

One of the realities of housing people with complex problems is taking action when people do not pay their rent or behave unacceptably. This is obviously something to be avoided – but they can often be a necessary part of someone’s journey. Recently, a former tenant came back to Hope into Action’s offices who we had evicted a couple of years ago, in order to pay back some of the rent arrears she owed. She said ‘Don’t feel bad for one second about what you did – it was the right thing to do and gave me the kick up the backside I needed.’

On the frontline, this is the kind of complex reality we work within. And the framework of grace and truth we can find a hopeful realism that has help sustain us and avoid the pitfalls of naivety on one hand and cynicism on the other.

I have learnt a lot from the 12 Step recovery movement. When I was at the West London Mission I would often sit in on the open AA meeting in the basement at Hinde Street Methodist Church along with 70-80 others. I was always struck by the grace shown in the radical inclusion for anyone struggling with addiction – there was no hierarchy – you would literally have film stars sitting next to people who are homeless. But this is grace as the basis for a community of raw truth telling. And this blend is what makes 12 Steps so effective.

Similarly, I have found grace and truth helpful in supporting family members, such as my cousin James who struggled with heroin addiction for over 20 years. We spoke regularly but I also maintained clear boundaries. We agreed that I would never, ever lend him any money because this would lead to his addiction ruining our relationship just as it had ruined so much in his life. Rather than limiting our relationship, this truthfulness protected and sustained it. Tragically James died aged 45, but I could speak at his funeral as one who had maintained a relationship with him and who knew him and loved him.

We need more engagement in other people’s lives, not less – but we need to be healthily honest about the challenges of staying close to people whose lives are chaotic or demanding. I have come to see wise boundaries as a bit like oven gloves – they enable us to handle things which are good and healthy but offer protection from harm.

And I know that the tension between grace and truth is so relevant to those engaged in all social action: debt prevention, food distribution, youth work, supporting those with mental health challenges, counselling and all pastoral work.

Our world is dying for authentic love. And the reason grace and truth are a strong foundation for social action is because they are the key components of love. God revealed this grace and truth to us in Jesus and the best thing we can do is reflect it to those around us.

Conclusion: the future for Christian social action

In his book Subversive Spirituality, Eugene Peterson wrote:

“This is an urgent time and the task of the Christian is to learn how to maintain that urgency without getting panicked, to stay on our toes without caving into the culture. This is not a benign culture where everything is going to be fine. Everything is not going to be fine.”

It’s a sober warning.

Great challenges face the world, our country, our communities and our own lives. I believe more than ever that the grace and truth of the crucified and risen Jesus Christ offers the deepest hope and surest foundation for meaning, purpose and the redemption we need.

So, with all I have shared in mind, I offer these 5 points for the future of Christian social action. The first three relate to the challenges I outlined earlier and there are two more.

1.Christian social action must be accompanied by a Christian model of justice

As Pope Francis has said ‘the church is not an NGO’ – we must resist being flattered for our usefulness, or instrumentalised as a service provider and recognise the distinctive and prophetic voice that the church is called to take at this time.

We stand at a crisis point in terms of homelessness and poverty. We cannot be content to prop up an unjust, neo-liberal system that favours big corporations and makes low wages, welfare dependency and foodbanks permanent features of our social architecture.

To reduce the need for food banks, debt counselling and emergency night shelters, increases to welfare benefits are not going to be enough. The underlying causes are more complex than handouts alone can fix – we need reforms and investment that will generate meaningful work that will enable people to have some self-respect.

Is the church courageous enough to challenge the new administration to reform an economic model that generates incomes too low to live on? We should seek a positive yet distinctive relationship with the government, be clear about what we agree on and be willing to challenge them on the underlying systemic problems. We need to speak truth to power.

We should avoid the ‘justice nostalgia’ of looking back 40 years to reports like Faith in the City; instead we need to consider what is needed now? This is a new time, for a new conversation.

2. Our social action must be empowering and build mutuality

We also need to look at ourselves and how we operate.

Poverty is about more than a lack of resources – it is also about relationships and identity. As Pope Francis puts it

‘Caring for the poor is more than simply a matter of hasty handouts; it calls for re-establishing the just interpersonal relationships that poverty harms’.

Alongside arguing for change at government level, we should shift our own emphasis – to approaches which help people into work, which generate enterprise, use skills and empower strengths. This means transitioning from food banks to initiatives such as Pantries and Community Groceries where people become members to buy discounted food with dignity – the development of which Frank championed. It also means social businesses which support people into work.

People are not helped by being passive recipients. Relationships are at the heart of what it means to be human – and best when two-way and full of mutuality. Transformation happens through reciprocity, where people are able both to receive and to give and contribute.

As well as speaking truth to power, we also speak truth to those who are without power – not to judge or demean but because it is truth that sets people free. Often this is a far harder task than just railing against the system.

Hope into Action’s frontline staff are called Empowerment Workers and recently one of our tenants, who had suffered terrible domestic violence said this to me:

‘My Empowerment Worker didn’t just give me a ladder to help me get out of the situation, she showed me how to build my own staircase.’

What can we do to help build their own staircases rather than rely on our ladders?

3. Social action should deepen its Christian distinctiveness

Lesslie Newbigin said ‘The business of the church is to tell and embody a story’.

Social action can help tell this story in a compelling way. But we must hold our nerve to integrate our faith and deepen the Christian distinctive.

In his memoir, Frank writes about the low-key approach he took to expressing his faith because he was concerned about it affecting his campaigning. Many of us prefer an implicit form of faith, expressed through what we do.

But this is a new time. And I believe the times call for social action agencies to be more explicit, to be bolder and more confident. In this period of great spiritual confusion that faith is not a private matter.

As Newbigin argued so well, the gospel is public truth (The Open Secret ,1995):

“The community that confesses Jesus is Lord has been, from the beginning, a movement launched into the public life of mankind.”

We do proclaim a privatised belief but a public truth.

Of course we must guard against any theological arrogance, but the bigger danger is that we are too anxious and timid. We need what Newbigin termed ‘proper confidence’ so we can tell our story about why we do, what we do.

And the challenge is inescapably personal. As Jim Wallis says

“Faith is always personal, but never private.”

Do we really believe that God is at work in the lives of those we serve? That knowing his saving love is consistent with the positive outcomes we want for those affected by poverty?

Here I want to show a picture of a recent baptism of one of Hope into Action’s tenants at Oakham Baptist Church. I know that full-immersion baptism may seem alien to many and may cause some instinctive reactions. But sit with it – and consider carefully what you see – I think this picture speaks a thousand words. Someone who has been through so much accepting the deepest offer of the church: a new identity in Christ within a loving community. This is the ‘Heineken effect’ of church: reaching the parts the voluntary sector never can.

4. Beware of superficiality and pay attention to messy realities

The language of “social justice” is increasingly popular in Christian circles but I am increasingly suspicious of those who speak fluently on platforms and social media about justice and without being anchored in the complexity of the actual work.

In a church affected by capitalist culture, “social justice” itself becomes a commodity and a superficial brand to wear and parade on social media.

Such superficiality means rather than engage with the messy realities we opt for simple narratives which turn people and institutions into ‘goodies’ and ‘baddies’. But real life is simply not like that.

The Church must stand against such superficiality. Bonhoeffer’s statement that “The person who loves their dream of community will destroy community” could be re-worked to say

‘Those who love their dream of social justice will undermine social justice.’

Rather than utopian dreams or ideological theologies, we need to anchor our concept of justice in real life and experience: in the broken, sinful reality of the world’s systems and people – and in our messy attempts to make the world better.

5. We need a new movement of Christian social action networks

Christian social action charities often operate in silos shaped by church tradition and denominations and don’t know each other or coordinate their work. The UK has never had a truly ecumenical social action network which brings together agencies from across the church spectrum. The closest thing to this was Faithworks which gathered thousands to their annual conferences in the early 2000s.

We need to rouse a genuine movement of people motivated by faith, working together for the Common Good. We need to listen to what God is doing within the Church, and most importantly what He is doing among communities and neighbourhoods trapped in poverty.

This is the approach Frank took – he listened to God and listened to the people of Birkenhead – responding with compassion but also courage and honesty. This is why his death caused such a huge outpouring of appreciation.

Conclusion

Thank you so much for listening to my thoughts and thanks again to Jenny for the invitation.

This is a time of critical instability across the West and a key time for our nation. Christian witness in word and action is needed more than ever – but our social action needs to grapple with the difficult questions about injustice, dependency and secularisation.

Who will we listen to, and how will we organise in ways that integrate our concern for justice, empowerment and faith?

The prophet Jeremiah (6:16) speaks of our need for discernment:

‘Stand at the crossroads and look; ask for ancient paths, ask where the good way is, and walk in it.’

Let’s be confident that this ancient path, this good way to walk, can be found in the grace and truth of Jesus Christ. As 1 John 3:18 puts it:

‘Let us not love with words or tongue, but with actions and in truth’

The lecture text can be downloaded from Together for Common Good

Discover more from Grace + Truth

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

BRILLIANT. Thank you so much Jon, much love to you and your family.

From Joy Willson

LikeLike

Thanks Joy – much appreciated

LikeLike

Thank you Jon for the great talk. If you heard any noise, it was me nodding my head in agreement. We will have to grapple with these issues this side of eternity, for we will be accountable to the Lord for how we behaved toward our fellow image-bearers.

LikeLike

Thanks Andrew for watching and your encouragement!

LikeLike

Fantastic article that I resonate and agree with 100% (not just 85% 😉 ). Thank you for your thought leadership in this area, based on depth of experience and such wisdom and balance. You’ve captured and reconciled so many thoughts and reflections that I’ve had over the last few years from my own experience, and in a way and with a clarity that I just couldn’t do. Thank you. This really is a message that the whole church needs to hear and engage with.

LikeLike

Thanks Marcus for your kind and generous feedback. I hope it can resonate and help people on a practical basis. God bless and thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person