Being a voice for change whilst meeting the needs of people at the margins

The 2025 Hook Lecture delivered by Jon Kuhrt, Leeds Minster on 21st October 2025. This is the video of the lecture which starts at 12 mins and below is the text:

Introduction: optimism or hope?

Firstly, a sincere thank you to the Leeds Church Institute for the great honour of inviting me to deliver this year’s Hook lecture. It’s great to be here with you all.

I start with a prayer:

Lord God revealed in Christ, be with us tonight through your Spirit. And may the thoughts of my heart and the words of my mouth serve you. May tonight help each of us to do justice, to love mercy and to walk humbly with you. Amen

The question that we are exploring tonight could not be more timely or more relevant. We are living in times of significant change, anxiety and anger. Consensus is breaking down, polarization breaking out and the evidence is seen both online and on our streets. Wealth and property are increasingly held by smaller number, our housing crisis deepens and trust and confidence in mainstream political parties is at rock bottom. Pope Francis described it as ‘not an era of change, but a change of era’.

These divisions are fueled by social media corporations making vast amounts of money from algorithms designed to appeal to the worst human impulses, feeding us a diet of content curated to play on our insecurities, bloat our own sense of righteousness and feed a collective addiction to anger.

W.B. Yeats’ famous lines seem even more relevant:

‘Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold.’

And I believe we should prepare for the situation facing our communities to get tougher. I don’t believe there is cause for optimism, but more than ever there is a need for hope.

I work for an organisation with hope in its name, Hope into Action, a Christian charity which works with churches to house people who have been homeless. Over recent weeks, it has been alarming to see the direct impact of these national tensions, especially related to immigration, affecting our frontline staff and churches and, worst of all, making our refugee tenants feel threatened and unsafe.

As I have constantly seen over the last 30 years, hope is a vital ingredient of transformation. Hope unlocks a sense that things can get better, that the future can be different to the past, that there is something to aim for, something to live for.

And I stand here tonight as someone convinced by the hope in Christ: this is not a vague sense that things will be OK, or a optimism founded in the goodness of humanity but a hope rooted in what God has done through Christ, what he is doing through his Spirit and what he will one day complete.

What does it look like to put Christian hope into action in today’s world? What is the Church called to be at this moment of turmoil and increasing poverty in our country?

Over the last 15-20 years there has been no shortage of church-based social action initiatives starting up such as warm hubs, debt centres and homeless shelters. And, most notably, food banks, a form of social action unknown even just 20 years ago. 77% of which are currently based in churches.

But the overall picture of UK poverty is deteriorating. In 2025, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation reports that over 21% of the UK population are living in poverty.[1]

In my area of work in homelessness, rough sleeping has risen 20% in the past year and there is currently a record 131,000 homeless households currently in temporary accommodation.

So despite the heroic efforts of volunteers, charities and churches, and despite the stream of advocacy campaigns vowing to “end poverty”, there are no signs of improvement and the trends indicate a further deterioration.

Therefore, I believe that the church’s social witness stands at a crossroads. Now is the time to grapple boldly and faithfully with the challenges our country faces and seek answers rooted in Christian hope.

We should not celebrate the growth of social action because it proves the church is useful. We need to draw deeper on our traditions and biblical theology, be self-critical, ask hard questions and carefully consider the right road to take in the next 20 years.

Are we content to just be providers of handouts or do we have something genuinely prophetic to say to our rich, polarized, unequal and angry country?

Tonight, I will start by unpacking a holistic understanding of poverty and the relevance of grace and truth. I will then talk about what it means to be prophetic providers and end with three directions for Christian social action for the future.

A holistic understanding of poverty

At the Greenbelt festival a few years ago, I was asked to lead a seminar titled ‘Getting real about homelessness’ and to speak about the importance of showing both grace and truth in making our help effective.

I was concerned that in a liberal-left environment like Greenbelt that everyone could be in danger of agreeing. We wanted to inject some tension so we mixed it up by getting an actor to pretend to be someone homeless and interrupt the seminar. As we started the seminar, he walked in, started mumbling discontent and swearing a bit and you could see ripples of discomfort affecting people. He strode up to the front of the marquee in front of about 300 people, grabbed the mic and told everyone that he was homeless and needed help now. He explained that he had jumped the fence because he heard there was a bunch of Christians here and he made a raw appeal for cash.

Two of us then did ‘impromptu’ speeches about whether we should give or not, and then we asked everyone in the marquee to physically move and go to one side or the other depending on whether they would give or not.

The stunt worked a treat – and it certainly created some tension. A lot of people simply didn’t want to move at all. It created something that is so often missing from seminars and conferences focused on social justice: grappling with the genuine tensions involved in helping others. And it led to a far more honest conversation than we would have had without it.

One of the people who got up to share his story in the discussion afterwards was someone called Chris who had been street homeless for many years as a drug addict and alcoholic. He told everyone his moving story of growing up in a tough area, joining the armed forces, experiencing trauma and then sliding into addiction after being discharged, his wife throwing him out and his 3 years sleeping rough and an attempted suicide.

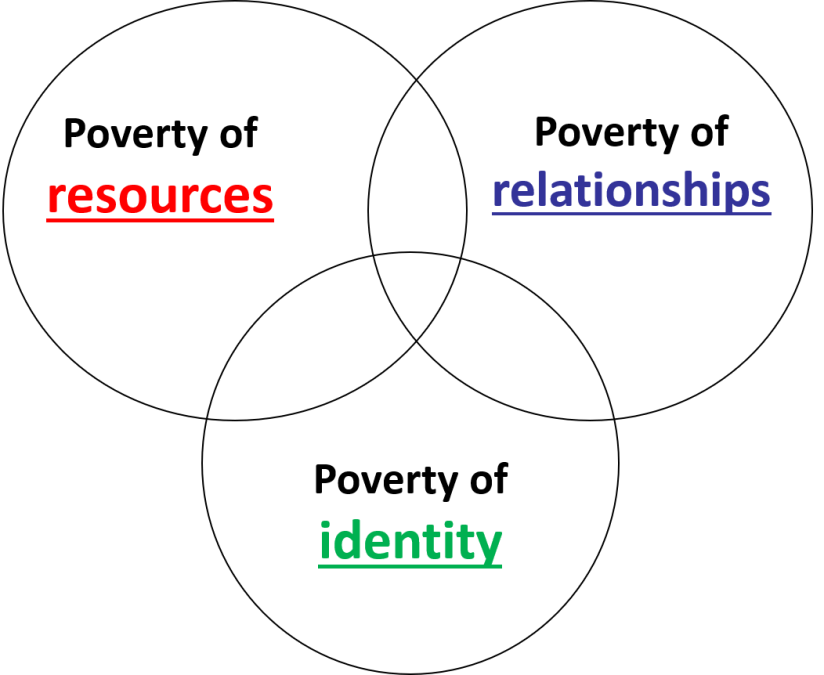

Chris’ story was the kind of experience I have heard countless times – it’s a story which illustrates the ingredients of poverty which affect our whole country but which are shown in extremis in homelessness:

Firstly, the poverty of resources. The most obvious factor is material poverty: cost of living, debt, unemployment, under-employment, the insecurity of zero-hours work and the gig economy. Most of all, there simply is not enough affordable housing. Too many luxury developments are built rather than the council and affordable housing we need.

Secondly, its also a matter of relationships. Every homelessness story includes broken relationships: so many have nowhere to go because they have no one to go to. Issues of domestic violence, abuse, family breakdown. Relationships are core to what it means to be human and isolation and loneliness are just as deadly as cold temperatures.

Thirdly, it’s a matter of identity. It is not just people’s relationships with others but their relationship with themselves which is often fragile. Low self-esteem, mental health problems and the addictions which are so connected, all undermine someone’s very sense of self. There can be an inner homelessness which is far harder to change than external needs.

Homelessness is not a stand-alone issue but an amalgam of many: a barometer of social need which illustrates political failure, community breakdown and personal tragedy. It is much more than house-lessness: houses are vital resources but homes are much more, they are places of relationship and identity.

As Chris’s life showed, an addiction affects all three: robs your resources, destroys relationships, scars your identity.

And this is why addressing homelessness involves more than simply allocating the resource of a flat: humans have needs that cannot be met by bricks and mortar alone. And this is why its not simply an issue that the government can solve – they can allocate resources but can do far less about the poverty of relationships and identity.

I worked as a Specialist Rough Sleeping Adviser for central government for 4 years which included the covid crisis. Even with the offer of a free hotel room, there was still 2000 people sleeping rough at the height of the pandemic. This was not simply down to a lack of resources or ‘their choice’ – it was due to chronic combinations of these forms of poverty: meaning there was not enough trust for them to accept the offer.

I believe that the church has the ability to respond to all three of these forms of poverty.

This is what Hope into Action does: we provide the resource of accommodation and the professional support to go with it – but also relationships through the friendship and community of a local church community, and the opportunity to transform your identity through employment, volunteering and faith. Please take one of our Impact Reports at the end which can tell you more.

Grace and truth

Let’s go back to my friend Chris. After 3 years on the streets and a spell in psychiatric hospital, he got a flat. But in terms of addictions, much of his life was similar to before. He started going to his local church, seeking food and money, but he was often demanding and abusive. People gave food and even baked cakes for him, but in Chris’ words, he was a bit of an arsehole.

But that local church did help him get his life back together and he was actually at Greenbelt because that church had brought him along.

What was fascinating, was that the most decisive thing the church did was not the obviously kind and compassionate things. Actually, it was the intervention an older lady, Doris, who had looked him in the eye one day when he was kicking off and told him what she thought. She said to Chris that he stunk, looked disgusting and that he should stop abusing himself and others and sort himself out.

It was Doris’ words which hit the spot and provoked him to take responsibility and change his behaviour. Chris has now been sober for 17 years and he counts his recovery journey as starting from that conversation. As he says:

‘Everyone else was nice but it was her truth which got me on the road to recovery.’

It was a brilliant personal illustration of what I had found in my professional experience over the last 30 years. At the start of John’s gospel, it says that Jesus

‘came from the Father, full of grace and truth’ (John 1:14).

The balance and tension between grace and truth is critically relevant to how we help others and for all social action. Have a look at this chart:

Many people start off thinking that helping others is just about focusing on the left-hand side. But this is naïve. These qualities are vital but they not enough by themselves. Almost anyone who has had any responsibilities – especially a family – knows the importance of the right hand side too.

This balance and tension has been enormously important to me in my work in the last 30 years. It has helped me make good decisions, maintain boundaries, avoid burnout, and focus on what is best for the people we are serving. It has also provided solid theological foundations for my work.

And meeting Chris has led to him becoming a family friend. We have also done a lot of work together, speaking engagements at St Paul’s Cathedral, Lambeth Palace and at Lee Abbey and we co-wrote a booklet called ‘Grace, Truth and Transformation’. Chris has volunteered for years in a local centre for rough sleepers and helps train psychology students in trauma and recovery issues for NHS.

We are called to love our neighbours, but a fluffy, sentimental type of love will not last long. And I have come to believe that the reason grace and truth are so vital is because they are the ingredients of love.

What does it look like to embody this thinking in our social action?

Prophetic providers

I like the title of the lecture tonight, but we should not accept the dichotomy it sets up between being prophets and providers. Everything I will share tonight has been learnt primarily from the front line of providing homelessness services for 30 years where these realities confront you every day.

And I believe we need to find a truly prophetic edge based on practical experiences. As Ernst Trolsch wrote:

‘We theorise and construct in the eye of the storm’

We learn from being involved in real lives of real people. We should be suspicious of academic theory or abstract theology which is detached from real experience.

We don’t need ‘prophets’ who have no experience of providing. However fluent they may be in talking, blogging or vlogging about social justice, their words need to be honed by the messy business of providing practical help. Keyboard warriors will not inherit the kingdom of God.

But equally, we don’t want to become providers who become wedded to the status quo because of their vested interests in the charitable models of help or their government contracts. We must resist the cosyness to the powers that be which compromises speaking the truth.

What we need is prophetic providers.

Four examples

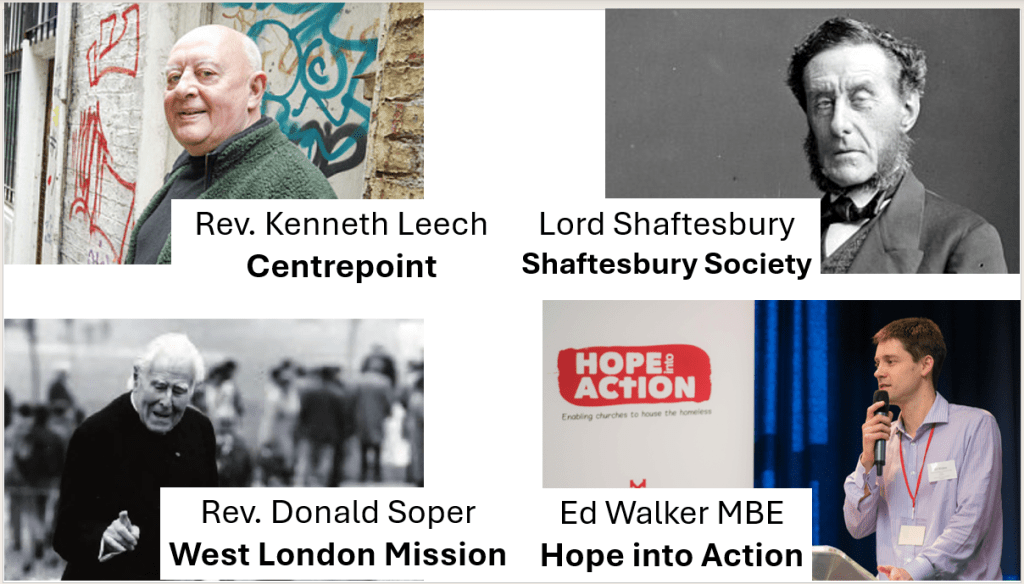

The best way to illustrate this is to speak about real people – and I think there is nowhere better than the four people who founded and led the charities I have worked for:

In the 1990s I worked for the youth homeless charity Centrepoint, founded by Rev. Kenneth Leech, a socialist and Anglo-Catholic Anglican priest who was a curate at St Anne’s Church in Soho in the late 1960s. He opened up the church’s crypt for homeless young people and they named it Centrepoint Soho as a prophetic statement against the huge office tower block called Centre Point just built at the top of Oxford Street but standing empty at that time for tax reasons. I became manager of the shelter on the St Anne’s site, read Leech’s books on sacramental theology and social action and got to know him.

In the early 2000s, I went to work for the Shaftesbury Society, a far older and larger charity which started life as the Ragged School Union under the patronage of the Victorian Lord Shaftesbury. He was nicknamed the ‘Poor Man’s Earl’ because of his tireless political struggle for factory reform to combat the child labour. As well as his political campaigns, Shaftesbury also championed a whole host of practical Christian mission in the urban slums. He left an incredible legacy of mission churches, services and schools for disabled people. Many people do not know that the famous angel statue at Piccadilly, erroneously nicknamed ‘Eros’ is actually ‘The Angel of Christian Charity’, erected in honour of Shaftesury.

In 2010, I moved to the West London Mission, a Methodist organisation formed in the Victorian age which ran shelter for rough sleepers, bail hostels for prison leavers, homes for pregnant teenage mothers and even starting the first ever creche for working mothers. And much of this work was developed by Rev. Donald Soper. Like Ken Leech, Soper was also an outspoken socialist who was famous for his robust outdoor preaching at Tower Hill and Speakers Corner. Over the course of his life it is estimated that he preached 10,000 sermons, and answered more than 250,000 questions. During the WW2 he was banned from broadcasting on the BBC due to his ardent pacificism and in the 1960s he became the first Methodist Minister to sit in the House of Lords.

And 2 ½ years ago, I joined Hope into Action, formed in 2010 by Ed Walker. Ed came back from working in Africa with Tearfund and was struck by the homelessness in Peterborough. When he received an inheritance, he and his wife chose to use it to buy a house for homeless people and to partner with the local Baptist Church. In the 15 years since, Hope into Action has grown into a Network of 131 houses across the country, all purchased by those who want to use their wealth as an ethical and impact investment. Our staff provide professional support and every house is partnered with a church who provide friendship and community.

All of these men were different: Soper and Leech sacramental socialists, Lord Shaftesbury an aristocratic evangelical Tory, but each of these men had prophetic vision for how the Christian faith could make a difference to poverty and homelessness in their era. All 4 were providers who inspired and oversaw practical work which was anchored in their faith and a vision of God’s kingdom. They did not simply preach, write books or set up Think Tanks: rather their faith was incarnated and embodied in providing practical help to people on the margins.

It is this integration of practical action, prayer and politics which will make us prophetic providers. This is what we need more than ever.

Three directions for the future of Christian social action

In 2023, I wrote an article published in Christianity Magazine titled ‘The sins of social action’ where I critiqued three disconnections in contemporary social action. These were:

- The disconnection between charity and justice

- Dependency: the disconnection with empowerment

- Secularisation: the disconnection with faith

I believe its these sins that cause Christian social action to slide into simply being providers and prevent us from the prophetic edge that we are talking about today.

I knew the article was onto something when so many people across a wide spectrum of theological and political belief liked and shared it – but all for different reasons.

Those on the left will always applaud talk about structural injustice but they get far more nervous talking about issues of dependency and personal responsibility.

The right often applaud charitable activity and emphasise personal responsibility, but want to give a free pass to the systemic failures of the market to provide adequate housing.

And across the board many social activists are both challenged but remain deeply nervous about calling out the problem of secularism and the loss of Christian ethos.

Being prophetic involves going beyond the accepted political silos and theological echo-chambers of left and right.

The prophet Micah (6:8) offers us a great structure in his response to the question

‘What does the LORD require? That we act justly, love mercy and walk humbly with your God.’

So in this last section, I will set out 3 directions for a more radical social witness that each respond to these 3 sins:

- The first is political – acting justly: looking outwards to challenge economic power

- The second is practical – loving mercy – looking inwards to how we run social action projects

- The third is theological – walking humbly with God – looking upwards to maintain our Christian distinctiveness

1. Challenging power: the call for economic justice

The Brazilian Catholic Archbishop Dom Helder Camara famously said:

‘When I give bread to the poor they call me a saint. But when I ask why the poor are hungry, they call me a communist’.

It’s a quote which captures the inescapable tension between charity and justice.

How does our social action question the underlying social and economic systems which create such need in the first place?

The crisis of homelessness highlights this starkly: there are more people homeless in temporary accommodation than since records began. In London councils alone, this costs the public over £5m every single day. The financial and human cost is appalling: earlier this month it was revealed that 1611 people died homeless last year.

These figures reveal the fundamental structural injustice of UK housing and our broken housing system. None of these problems will be solved by voluntary action alone. And the church should never be reduced to the handmaid of the State, running around filling in gaps caused by government neglect and market failure. We must not be seduced by either the lure of feeling useful.

The two key themes of the biblical prophets were idolatry and injustice – and we see both of these problems in our contemporary housing crisis.

Houses have become idols which society worships. Rather than affordable housing, we see luxury new housing developments popping up all over our cities. Local to me there is the abomination of Battersea Power Station – a former public asset providing power to the capital has been turned into a soulless luxury block of expensive flats surrounding high-end shops. It’s the opposite of what South London needs. At the same time, even couples who are both working struggle to afford decent accommodation.

We also need work which pays, and which gives the dignity that employment should provide. Market dominance has reduced people to mere units of labour, manipulated for profit. It has been a disaster for stable community and for family life. We need to demand an economy which generates decent, dignified employment rather than depends on welfare. Poverty cannot be ended while a low wage, high welfare economy remains in place.

And we need a welfare system which incentivizes work. At the moment we have dependency and negative incentives baked into our benefit system. The late Labour MP Frank Field coined the term ‘Benefit trap’ which he said is “a full frontal attack on a working class moral economy that believes in work, effort, savings and honesty”.

The inequality gap in the UK continues to grow, with the top fifth owning two thirds of the wealth, and the bottom fifth only 0.5%.[2] Our focus needs to be on the unjust political economy which perpetuates such inequality.

I find it tragic that in recent years, “social justice” came to be more associated with identity politics than economics. Often this is a cheap and performative form of social justice – it enables large corporations to claim ethical points by using a logo or kitemark rather than addressing the pay and conditions of their cleaners and contractors. We need to speak truth to power – and its economics where the power lies.

2. Changing practice: empowerment and the contributory principle

Secondly, those leading social action projects need to look at ourselves and our own practices.

The hard truth is that not all responses to poverty are helpful or effective. A huge amount has been learnt in the last few decades about what helps Majority World countries overcome poverty. The book Dead Aid by Dambisa Moyo argued powerfully that ‘aid’ given from richer countries actually served to disempower economies and deepen poverty.

And the US Christian activist Robert Lupton argues in his book Toxic Charity that too often social action deepens problems by creating dependency and destroying personal initiative:

‘When we do for those in need what they have the capacity to do for themselves, we disempower them.’

Lupton makes an important distinction between crisis situations and chronic problems:

‘We respond generously to stories of people in crisis, but in fact most of our charity goes to people who face predictable, solvable problems of chronic poverty. An emergency response to chronic need is at best counterproductive and, over time, is actually harmful.’

The ‘crisis’ approach is easy to fall into because projects which provide a one-way exchange are straight-forward, easier to set up and popular with volunteers. But over the years I have been increasingly concerned to visit soup runs and churches where armies of the well-meaning middle-class are running around serving people who are turned into passive recipients.

And the biggest need in homelessness is not to give away more resources but how we can help people maintain their accommodation, pay their rent, form positive relationships and use their skills and strengths.

Catholic Social Teaching has much to offer. As well as the principle of solidarity with the poor, there is the principle of subsidiarity – that responsibility is taken at the appropriate level, empowering people to help themselves. As Benedict XVI said:

‘Subsidiarity is first and foremost a form of assistance to the human person.. [which].. respects personal dignity by recognizing in the person a subject who is always capable of giving something to others.’[3]

The uncomfortable truth is that too much of the growth of social action has been focussed on giving out resources and often this work is digging a bigger hole for the people it is seeking to serve. I have come to believe that running a class to help 10 people cook for themselves is better than giving out free food to 100 people.

We need to develop models of help which have empowerment and reciprocity at their heart. A good way of expressing this is the contributory principle: all forms of social action should empower beneficiaries to contribute to their own welfare and to help others.

In food poverty initiatives, this means that beneficiaries will pay something towards the food they are receiving. In homelessness services, this means focussing on empowering people to pay their rent and contribute to their own recovery. People are not transformed primarily through what they receive for free but through what they participate in and contribute to.

I believe the social commentator Darren McGarvey is a contemporary secular prophet. His book Poverty Safari shares his journey of homelessness and addiction and is the best book on poverty I have read because he is willing to talk about both structural injustice and personal responsibility. He wrote this:

“We deny the objective truth that many people will only recover from their mental health problems, physical illnesses and addictions when they, along with correct support, accept a certain level of culpability for the choices they make. Yet such an assertion has become offensive to our ears despite being undeniably true…Many of the conditions of my life began to change when I got less offended by the truth: some of my problems were mine to solve.”

Too often Christian social action shows a form of grace which is detached from this kind of truth. And grace without truth becomes what Dietrich Bonhoeffer described as ‘cheap grace’.

As well as speaking truth to power, we also need to speak truth to the powerless. Not a truth which condemns or castigates but which helps find them find dignity and liberation. The truth which sets people free.

3. Deepening spirituality: confidence in our Christian distinctiveness

Finally, I believe we need to look upwards to God – and to renew a commitment to a more distinctive Christian commitment in our social action.

The missionary Lesslie Newbigin has been the most significant influence on my theology. As a student, he volunteered on a Christian mission helping unemployed Welsh miners but the initiative had a strict liberal ethos which excluded any religious elements. Newbigin writes:

“as the weeks went by, I became less and less convinced that we were dealing with the real issues…these men needed some kind of faith that would fortify them for today and tomorrow against apathy and despair. Draughts and ping-pong could not provide this…they needed the Christian Faith.” (Unfinished Agenda, 1993)

Newbigin wrote many insightful books, but the challenge of this simple phrase ‘draughts and ping-pong could not provide this’ has always stayed with me.

One of the constant issues I have witnessed in the last 30 years is the slide into secularism that affects so many Christian organisations and projects. The homeless sector is packed full of agencies which used to be Christian.

Sometimes faith fades due to a lack of passion or confidence. Sometimes it is due to fear about what funders think. Sometimes it becomes fossilised when a charity’s founding inspiration is neglected. Sometimes its based on a false premise of bible-bashing and coercive practices.

It means that often, rather than something dynamic and creative, faith often becomes just a slightly embarrassing footnote in the history of an organisation. The fruit of action becomes separated from the roots of faith from which it has grown.

In 2013, the social research agency, Lemos & Cranedid a survey of homeless people which revealed how significant issues of faith and spirituality were to so many of them. Their report Lost and Found said that the ‘secular orthodoxy’ of the homeless sector more reflected staff perspectives than the homeless people themselves. The author, Carwyn Gravell, was an atheist so this could not be dismissed as Christian propaganda – and this was independent evidence of the deep relevance of faith and spirituality.

To use Paul Bickley milk-metaphor in his excellent booklet ‘The Problem of Proselytism’, too often faith is ‘skimmed out’ of social action.

I have spent most of my working life at the skimmed and semi-skimmed end, but I felt called and excited to work for Hope into Action because of their full-fat approach. We make no secret of our enthusiasm for integrating passionate faith within a professional working practice.

Faith in Christ is our engine: it’s what motivated Ed Walker to use his own money to buy our first house and what has motivated others to invest over £32m in houses. It’s why last year we had 430 people come to our conference, its what motivates staff to work for us and it’s what motivates churches to offer friendship to our tenants.

And most critically, faith is so relevant to the recovery journey that so many of our tenants are on. Last year 60% of our tenants wanted to be prayed for and 14 got baptized or made a formal commitment to Christ.

Susie is on the front page of our Impact Report. She is a former drug addict, someone who has slept rough and been in prison and now a HiA tenant. She has been on a wonderful journey and is actually speaking at an event at the V&A Museum today.

Here she is, surrounded by her church family and a few weeks ago she decided to be baptised. The church has provided her with the resource of a house and relationships of community – and she has taken the step of a new identity in Christ.

And being openly and confidently Christian does not mean abandoning professionalism. Our full-fat faith has not stopped us winning awards from secular bodies such as Homeless Link, The Centre for Social Justice and The Guardian.

The challenging times call not for shy Christianity but boldness: many young people are being drawn back into church at this time – recently at my church we had 5 baptisms on one Sunday – all young people in their 20s. They have found something compelling on which they can base their life – does our social action provide this? I love Donald Soper’s words on this:

‘Goodwill on fire, goodwill lit by the love of God, and its glow maintained by fellowship with Jesus. I know of no better description of the Christian Life.’

We need to stoke this fire of faith rather than allow it to dwindle. Social action should illustrate faith, not mask it. We need more of this ‘goodwill on fire’ and more full-fat faith.

Closing words: ‘the great disrupter’

I started off the lecture talking about the problems our country faces. Like Joseph’s dream about the coming famine in Egypt, I believe the next years could get increasingly challenging when it comes to poverty, homelessness and community conflict.

We do not have cause for optimism – but we must be people of hope.

Lesslie Newbigin was once asked about whether he was an optimist about the future and he replied:

‘I am neither an optimist nor a pessimist. Jesus Christ is risen from the dead.’

What did Newbigin mean? Well, rather than vague feeling that things will be OK, we can build communities of hope forged on Christ’s resurrection, the first-fruit of what God will one-day complete in the New Heavens and New Earth. This is our hope.

I believe the radical founders of many charities would be dismayed to see how the charity sector has been co-opted as arms of the state. The word ‘charity’ and ‘voluntary sector’ have become misnomers because they are so dominated by state funding – many charities are more concerned by the size of their turnover than societal change. ‘Third Sector’ conferences are not places for genuine debate but where the same, safe mantras are trotted out and organizational egos swell.

Christian social action should stand distinct and should seek to shake the status quo through political voice, practical action and prayerful discipleship. In the words of Jacob Dimitriou|:

‘Christian social action should once again become the great disrupter’.

We need radical solutions which speak to the root of the problems we face and not settle for the shallow waters of sticking plaster solutions.

Being prophetic involves holding together and integrating that which the world cannot: justice, mercy and walking humbly with God. We need to be willing to challenge across the boundaries of theological echo-chambers and political tribalism.

We need a holistic understanding of the material and relational poverty that plagues our nation.

To speak about both the grace and truth of Jesus and to live this out through our social action.

To call for structural change and personal responsibility.

For a more just political economy and more stability in family life.

To proclaim good news and to live this out practically.

To speak of both justice and Jesus.

To be both prophets and providers.

[1] Joseph Rowntree Foundation, UK Poverty 2025: The essential guide to understanding poverty in the UK

[2] The Equality Trust, The Scale of Economic Inequality in the UK, 2025

[3] Benedict XVI, Caritas in Veritate [2009, #57]